How to Orchestrate a Credible Homicide Reenactment

The 1985 race tinged Sagon Penn murder case (People v. Sagon Penn, CR74094) gripped San Diego over two years before culminating in mistrials and acquittals. The tragic outcome left one police officer dead, another permanently impaired, a civilian ride-along passenger wounded, and a defendant who later committed suicide. Thirty-six eyewitnesses testified ranging in age from pre-teen to elderly. The shots were captured on a recorded 9-1-1 call, which in the pre-cell phone camera era was remarkable. At trial, there were open questions what actually happened and which witnesses and experts were credible. A defense video reenactment and photographic visualization answered some.

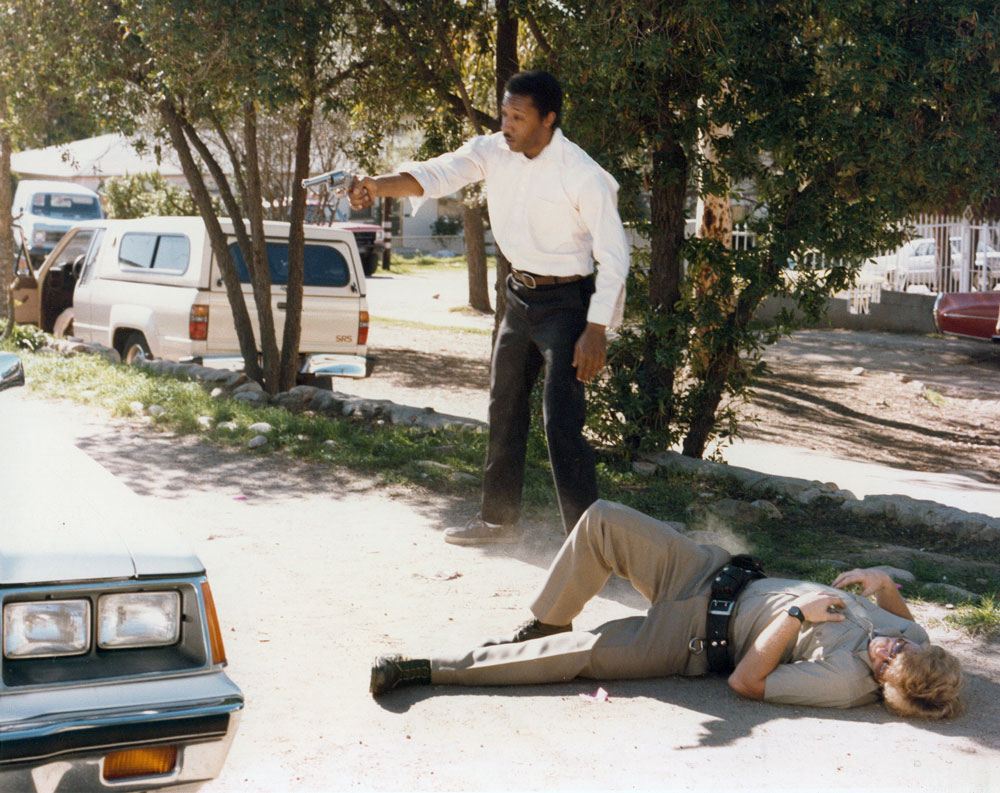

A “patented San Diego day.”

The incident occurred at the end of a warm and sunny afternoon, on what local weathercaster Lou Roen termed a “patented San Diego day.” San Diego Police Officer Donovan Jacobs stopped a pickup truck carrying several black youths driven by 23-year old Sagon Penn ostensibly for performing an illegal U-turn. Penn drove his vehicle down a lengthy dirt-covered driveway in Southeast San Diego and Jacobs pulled in behind him. Their heated exchange and scuffle drew the attention of several nearby residents and over two dozen parishioners existing a neighboring church.

Jacob’s backup, Officer Thomas Riggs, arrived and parked behind the Jacobs patrol car. As he exited his vehicle, he told civilian ride-along passenger Sarah Piña-Ruiz to remain in her right front seat.

Out of control.

The confrontation between Penn and Jacobs, who fancied himself a gang specialist, quickly got out of control after Penn handed his wallet to Jacobs and attempted to walk away. Jacobs reportedly attacked Penn with his baton while Penn, a brown belt student in Tae kwon do, fended off several blows. Eventually, Jacobs forced Penn onto his back perpendicular to the driver’s door of Riggs’ vehicle.

Eyewitness accounts differed but several recalled Jacobs cussing at Penn and calling him racial slurs. At some point Penn reached with his right hand to Jacobs’ right side, withdrew a revolver from the officer’s clamshell holster and pointed it at the left side of Jacobs’ neck, purportedly pleading with Jacobs to stop hitting him.

Reacting to his partner in trouble, Officer Riggs, standing behind Penn’s right shoulder, reportedly kicked Penn’s right arm causing him to fire the weapon. The bullet entered Jacobs’ neck, temporarily paralyzing him. Still supine, Penn turned his head and weapon toward Riggs whose right leg was raised, possibly while kicking. Fearing he would soon be killed by Riggs, Penn shot at him three times. One bullet went through the toe of Riggs’ right boot and another nicked his femoral artery.

With both officers down and incapacitated, Penn stood and glimpsed into Riggs’ vehicle through the closed driver’s window. Partially obscured by dust and the reflected sky, Penn said he thought Piña-Ruiz was a third officer. Fearing he was about to be shot by her he fired his last two rounds into the window, grazing Piña-Ruiz’s front and back.

Penn than commandeered Jacobs’ vehicle and exited the driveway, running over the fallen Jacobs. He drove to his grandfather’s house and told him he “shot three cops who were trying to kill him.” The grandfather drove Penn to the police station where Penn surrendered.

Immediate aftermath.

I was engaged the next day by Penn’s lawyer to interview Penn and document the crime scene. As a licensed private investigator, I was allowed access to Penn in County Jail where I photographed his baton injuries and learned he had yet to grasp the seriousness of his situation. I visited the scene and decided to engage civil engineers to survey it, which at the time was rarely done by the defense nor SDPD. I interviewed witnesses and by week’s end processed the scene. For the survey, I rented a Ford Crown Victoria and placed it where Riggs’ vehicle was found.

Enter Milton J, Silverman, Jr., Esq.

About a month after the shooting, Penn’s family hired noted local attorney Milt Silverman as lead counsel. I had worked previously with Milt on other high-profile cases and knew he was a detail oriented. Together with his forensic scientist, the late Richard G. Whalley, we examined Riggs’ vehicle in impound to determine the mostly likely entry point of the first bullet through the driver side window, which gave us an approximation of the angle of the weapon.

The first trial.

Penn’s first trial started nearly a year later, and my primary role was producing demonstrative exhibits, including a wall-size scene diagram, and coordinating the production of a video and photo reenactment of the shooting supervised by Mr. Whalley.

The crime scene driveway had been resurfaced since the date of the shooting so positioning a vehicle at the proper angle to the sky was not possible in the as-is condition. However, the civil engineers who surveyed the scene directed grading of a portion of the area to precisely restore the surface to its previous configuration and properly place a rental car to match the position documented during our scene examination the year before. With the vehicle properly positioned, we were ready to reenact the crime. But the weather did not cooperate.

Three days later the skies cleared and after adjusting our timing astronomically for the delay, we were ready to document Penn’s view into the car of a model dressed similarly as Piña-Ruiz. But first, we reenacted the shooting. It took several takes to get the amateur actors’ timing down, but we captured the action to the criminalist’s satisfaction. After, we set cameras up with transparency and negative film to photograph Penn’s view inside the vehicle. At the precise moment one year and three days after the 9-1-1 call recorded the first shot, we took our photographs.

Milt Silverman later told the jury, “we literally charted the heavens and moved the earth” to get it right.

The Rule of Evidence.

Sometimes, deception is unintentional or pushes advocacy to its limits, but is not improper within the rules of evidence.

Federal Rule 403 states, “Although relevant, evidence may be excluded if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading the jury, or by considerations of undue delay, waste of time, or needless presentation of cumulative evidence” (emphasis added).

Laying the foundation for the defense reenactment.

Through my testimony in trial, the defense successfully introduced a display photograph replicating Penn’s view through a closed driver-side window of a model posing as Piña-Ruiz partially obscured by reflected sky. We took these precautions to ensure the integrity of the demonstrative exhibit:

- the photo was taken at the scene a year later under the same weather condition and timed astronomically to the exact minute and second of shots recorded on the 9-1-1 call;

- the actor portraying the ride-along was dressed identically as the victim;

- the same make and model of vehicle was used;

- the angle of the door glass to the ground was calculated by licensed civil engineers;

- the camera position matched the most likely height and angle of Penn’s eye position at the time of the first shot based on the expert criminalist’s measurements from shattered glass remnants in the door frame; and

- photos were taken on color transparency and negative film, so the display print exposure could be matched to a control image not susceptible to exposure variables in the printing process

“One of the biggest frauds thus far perpetrated on this court and jury” part one.

The prosecutor vigorously objected to both the video reenactment and the reconstructed view from Penn’s perspective, accusing the defense of attempting “one of the biggest frauds thus far perpetrated on this court and jury.” (Mellin, 1986) The trial judge allowed the exhibit into evidence and suggested that the People might want to offer a photo of their own during rebuttal. They did. Mr. Silverman withdrew the reenactment video because, oddly, the prosecution argued it was incomplete because we failed to reenact Penn driving over Officer Jacobs.

Mr. Silverman did not care about the getting the reenactmnet video into evidence because its primary purpose was to confirm for the defense team all six shots did occur within a six-second span. This was to impeach a key prosecution witness who testified Penn uttered “you’re a witness too, I have to kill you” before shooting Piña-Ruiz. After the prosecution conceded the timing of the shots, displaying the video in court was not necessary.

In rebuttal, the prosecution offered their own version of what Penn perceived looking through the car window. It looked very different because the model inside the car was in uniform unlike Piña-Ruiz and the lighting, sky reflection, and vehicle angle were incorrect (only the defense regraded the driveway). The prosecution’s takeaway was clear: visibility was good enough inside the car that the defendant could never have confused non-uniformed clothing for a uniform. The judge admitted the photo and the prosecution believed it successfully neutralized the defense demonstrative.

“One of the biggest frauds thus far perpetrated on this court and jury” part two.

Trouble for the prosecution began the next day after the jury began deliberation. Silverman received a call the night before from an employee of the commercial photo lab that printed the People’s exhibit. She told him the police evidence technician who took the People’s photograph instructed her, while in the darkroom, to lighten the interior of the car to make the uniformed model more visible. The lab employee didn’t think that was proper but she altered the exposure as instructed.

Silverman informed the court of the blockbuster call, but the judge denied a defense request to inform the jury about the deception. The jury acquitted Penn of murder and deadlocked for acquittal of voluntary manslaughter, involuntary manslaughter, and attempted murder of the ride-along.

In the subsequent retrial, it was Silverman who entered the prosecution’s photo into evidence and grilled the evidence tech on the stand, implying he had the tech’s written instruction to alter the exposure in a closed envelope he waved in his hand. The tech admitted he instructed the lab to doctor the image. Silverman’s envelope contained an unfilled form.

The jury acquitted Penn of voluntary manslaughter and attempted voluntary manslaughter and deadlocked on involuntary manslaughter and assault with a deadly weapon. The prosecution did not seek a third trial.

Lessons learned.

In this case, the defense expended considerable effort to ensure the integrity of the scene documentation, homicide reenactment, and the demonstrative evidence while the prosecution’s case was jeopardized by a lone wolf technician who fabricated evidence in quest of a conviction.

Ultimately, trial counsel has to trust its providers to maintain the highest standards of ethical conduct, but steps can be taken before any demonstrative evidence is introduced:

- Understand the methods and mechanisms used to develop the content

- Vet your experts and providers in advance: what is their experience establishing a proper foundation for similar work?

- Request a foundation report or sworn declaration by the provider in advance of trial describing how demonstrative exhibits were produced

- Critique the work from your opponent’s perspective: how would you impeach the sponsor or prevent admissibility?

When you suspect your opponent’s demonstrative evidence or exhibits might be deceptive or compromised:

- Don’t jeopardize a cooperative relationship by nitpicking minor problems; reserve vigorous opposition for demonstratives that might hurt your case

- Prepare your attack carefully; solicit expert input to identify fatal flaws and alternative options

- Cross examine sponsors of suspected deceptive demonstratives thoroughly and respectfully to determine if deception was intentional or the result of accidental error or omission.

- Prepare a correct alternative version and sponsor it through your expert

Jim Gripp is a pioneering founder of Legal Arts, Inc. He has over forty years-experience as a litigation graphics consultant and private investigator. Email Jim at jgripp@legalarts.com.

Endnote

Mellin, Maribeth, “The People vs. Sagon Penn, Beyond Black and White: Part I: The Case for the Prosecution,” San Diego Magazine, Vol. 38, No. 11, Sep. 1986, p. 227