Powerful Visual Advocacy for Criminal Defense Mitigation

The backlog of criminal cases caused by the pandemic is so enormous, defense lawyers need help resolving cases before trial.

An innovative new tool appropriate for some cases and clients is the visual mitigation package. This immersive product focuses government decision makers on the accused’s human side, induce empathy, and propose alternative outcomes.

The civil litigation precedent

Until the mid-1980s, plaintiff personal injury lawyers used mostly written settlement brochures to negotiate resolution.

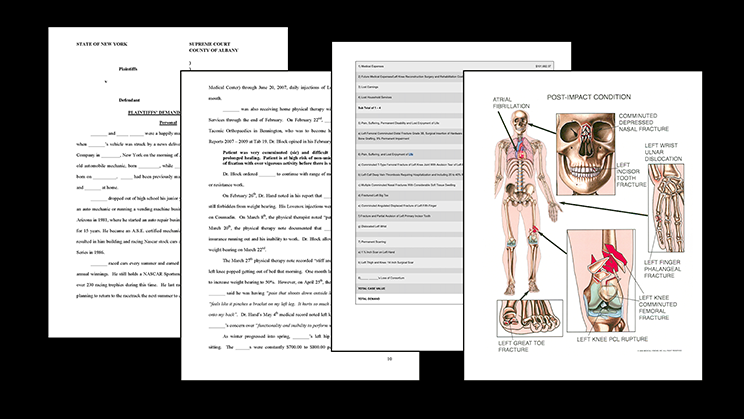

Typically assembled in a binder, these brochures comprised static photos, medical illustrations, accident scene diagrams, documentary evidence, deposition transcripts, expert opinions, and damages calculations.

The desired takeaway after reading the brochure was settlement was a viable alternative to trial.

Then well-funded contingency-fee counsel innovated video settlement brochures. By adding news video, reenactments, and interviews with the victim, family, friends, doctors, and experts, production values rose, and the persuasive impact of the brochure became stronger.

The desired takeaway after watching the tape was the gamble of going to trial was too risky.

The criminal defense status quo

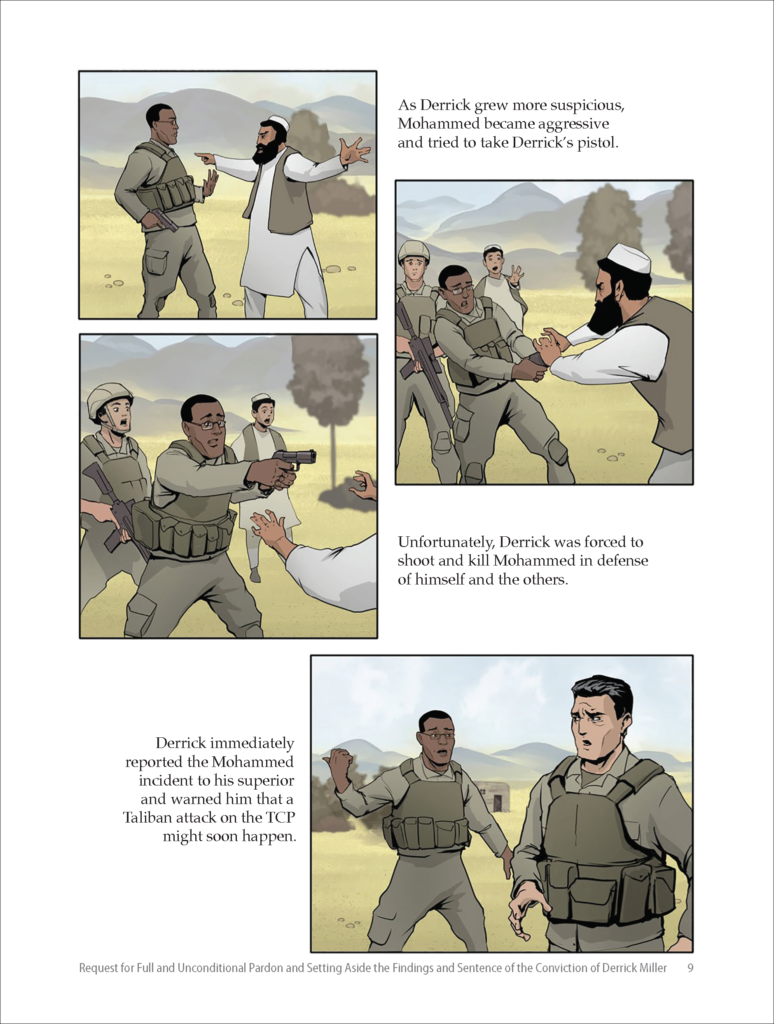

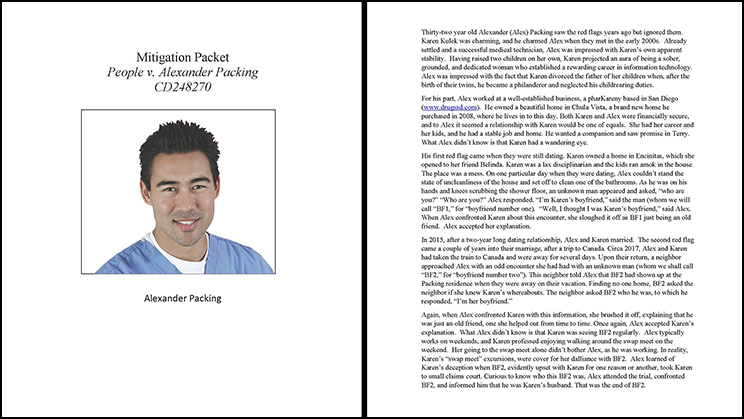

Criminal defense lawyers also produce a variation of the settlement brochure called a mitigation package. A mitigation package might include a sympathetic client story, psychosocial assessment, medical report, positive character testimonials, acknowledgement of culpability, a sincere apology and remorse, and a proposal for an alternative outcome less severe than the government’s threatened charge or sentencing guideline.

However, because of lack of funding or imagination, mitigation packages are still mostly written. The expectation by defense counsel is the prosecutor, probation officer, or judge will study the document, read the supporting materials, and carefully weigh the proposal in the interest of justice. In far too many cases, this does not happen.

Are written mitigation packages ineffective? On the contrary, but they require exemplary writing skills to induce empathy and the fortuitous alignment of facts to enable justification of an alternative outcome.

Trial – but when?

The fallback to an unsuccessful pre-trial mitigation effort is trial. That’s traditionally the first opportunity for the defense lawyer to employ her persuasive powers of withering cross-examination, impassionate argument, and personal charm to convince at least one member of the jury (in most states) to decide the government failed to prove its case.

However, during this pandemic the courts have substantially delayed trials so, criminal defense counsel must employ every advocacy tool available to resolve cases sooner than later, especially for incarcerated clients housed in dangerously overcrowded jails.

An example

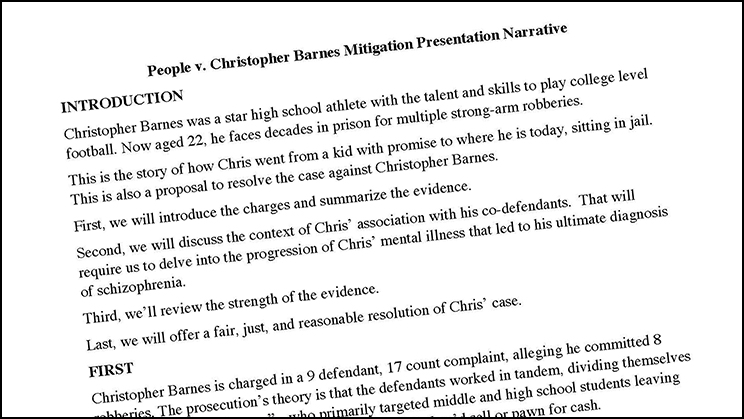

Recently I helped criminal defense attorney Brian J. White in San Diego prepare to negotiate a plea agreement for his client who was facing 42 to 65 years imprisonment for perpetrating eight strongarm street robberies. On a no-bail hold, the client was about to start his second year in jail awaiting arraignment.

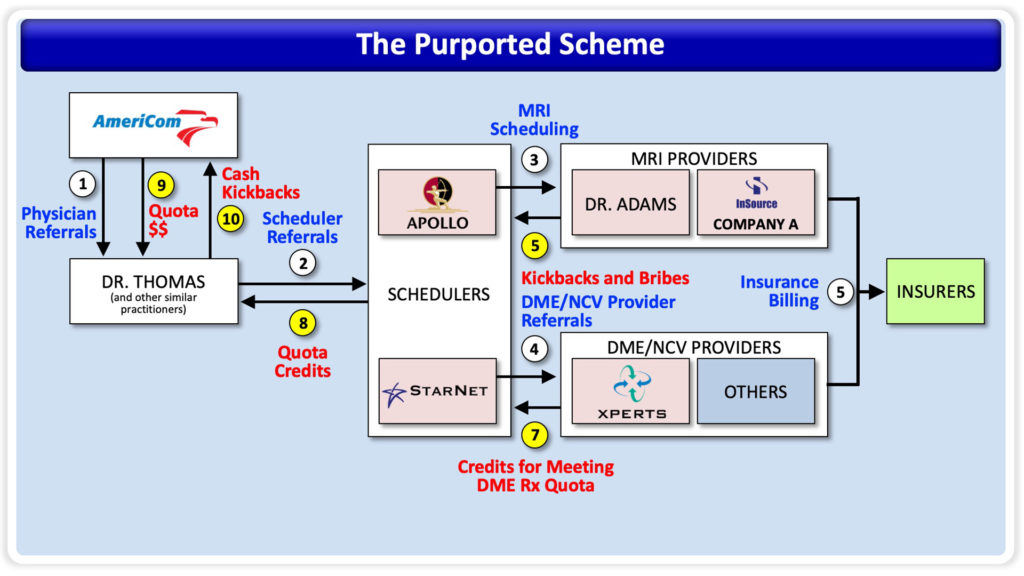

The accused, a member of one of two crews working the city and suburbs of San Diego, was scooped up with the others, all purported members of a Crip gang set, and charged with multiple felonies. He is white, 22 years-old when arrested, and was allegedly the wheelman for the crew, driving them to robbery locations and a pawnshop.

Brian needed to tell a compelling story why his client—a promising former high school football star with mental illness and a proverbial fish out of water in the gang setting—was actually a victim of exploitation by his cohorts instead of a hard-core gangbanger deserving decades in prison.

But with COVID cases increasing over the summer, the district attorney’s office suspended personal meetings with defense counsel and instead invited submission of materials for consideration.

An early opportunity for visual advocacy

These two factors, combined with the length of the client’s jailhouse incarceration and prevailing opinion the situation would not likely improve for months, was strong motivation to aggressively sell a pre-plea case to the government. I recommended a client documentary following the video settlement brochure model.

In a matter of weeks, we perfected a script describing the client’s story, collected photos, videos, and documentary evidence, created maps, and filled in gaps with stock imagery. In a matter of weeks, we perfected the script, collected photos, surveillance videos, documentary evidence, created maps, and filled gaps with stock imagery. After laying a narration track, I edited the deliverable to a TED-talk length 18-minute production.

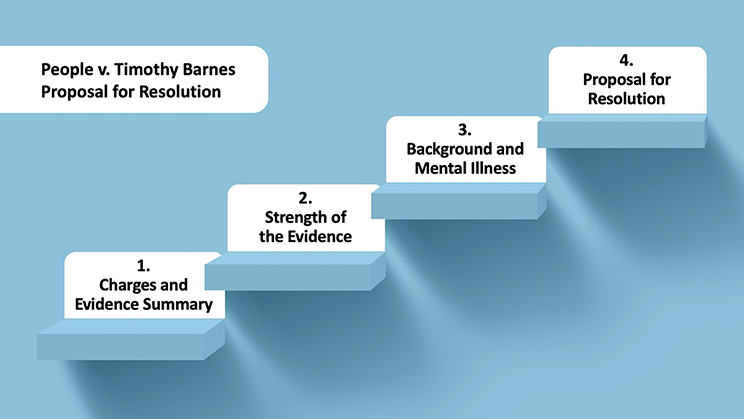

The show was organized into four chapters: charges and evidence summary, strength of the evidence, background and mental illness, and proposal for resolution. However, COVID thwarted our proposal for a confirmed diversion plan and alternative to incarceration because such programs required an in-person assessment.

But we received very positive feedback about the package from the prosecutor who said, “it was like watching a Dateline episode.”

Expert feedback

In a recent national Zoom forum of eminent mitigation specialists who routinely work capital and serious white-collar cases we discussed visual content for mitigation presentations.

Unfortunately, visually immersive mitigation packages like the one I produced for the robbery case, aren’t commonly used. Perceived cost is a culprit. One beleaguered public defender recalled a superior admonishing her for producing a “fancy” presentation for fear judges might grow accustomed to such productions from public agencies with limited budgets.

Because cost is always a high priority in criminal defense, retained white-collar and serious blue-collar or capital cases are more likely to afford budgets in the typical $3,000 to $5,000 starting range for professional documentary or sentencing videos. By necessity, public-funded cases need a less expensive homegrown option

Do-it-yourself

With a little self-training, the enterprising lawyer, paralegal, or investigator on a shoestring budget can produce a compelling client story and visual mitigation package for pre-plea and pre-indictment negotiation, trial, pre-sentencing advocacy, post-conviction relief, and clemency. Here’s how.

Start with the script

The process starts with a conventional narrative adapted into a script or screenplay, organized by topic and built with words and images.

As your client’s story evolves, you’ll identify which parts can be illustrated with existing images or custom content, and gaps to fill with stock imagery or clips of lead counsel speaking to the camera.

Choose the best medium

Next, select the medium that meets the decision maker’s need. PowerPoint might be the best choice for a live presentation.

A video documentary accessible by password-protected video stream or cloud-based repository is an option to substitute for or supplement a written submittal.

And “hard copy” content on a thumb drive or DVD is easily filed, copied, and distributed internally at the prosecutor’s office.

Visual and audio content can be edited and assembled differently, giving you a lot of flexibility for both delivery and repurposing in other stages of litigation.

PowerPoint

PowerPoint is a familiar tool to lawyers and can be used for scriptwriting and presentation. On-screen editing is easy, and because PowerPoint design is graphic design, a “script deck” can be refined and enhanced into a polished deliverable. Here are a few design tips:

- Make one point per slide but don’t cram information just to complete your point; slide count is irrelevant so use more slides to avoid crowding.

- Restrict bullet lists to essential content, write single short sentences, and show no more than 5 per slide; build content instead of showing it all at once.

- Don’t feel obligated to fill “empty” space by stretching or squeezing images into unnatural shapes; whitespace is the designer’s friend.

- PowerPoint slide templates serve a useful purpose for non-designers, but not every slide must conform.

- Improve PowerPoint performance by using standard fonts.

Video

Reflecting social media trends, people prefer new content presented fast, concise, and visual. Compared to written material, video is more efficiently consumed, less taxing on the viewer, and more interesting and memorable.

Mark Silver, the author of “Handbook of Mitigation in Criminal and Immigration Forensics” observed prosecutors are overwhelmed with well-meaning documents from defense lawyers that are too time consuming to read.

So, while a written mitigation package condensed into fewer pages is good, a narrated video production will engage the skeptical viewer to the conclusion and prompt better recall while deliberating your proposal.

How to engage the viewer

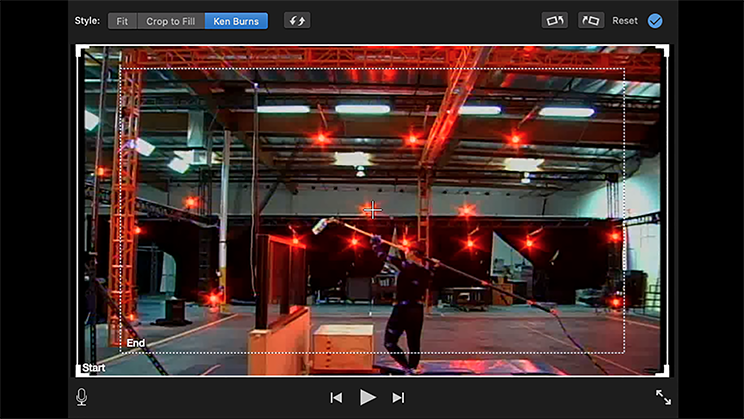

Motion: viewer engagement increases when on-screen motion is nearly constant. Ken Burns popularized entertaining documentaries based almost exclusively on photographs and interviews. His epic 11-hour, 9-episode “The Civil War” captivated viewers with over 3,000 static images by panning side-to-side, up-and-down, and zooming in and out. And while he did not invent these techniques, they are sometimes called “Ken Burns effects.”

Narration: all documentary videos feature voiceover narration, driving the pace for a seamless viewing experience. For about $100 you can buy a decent audio set up and do it yourself.

Scene changes: professionally produced documentaries change scenes about every five seconds. That’s an aggressive goal and you’re certainly not obligated to do that.

Rich content: some producers like to use stock imagery to drive an editorial point home or demonstrate a thematic topic like abuse, mental illness, or remorse. Others prefer just case-specific content and rely on interviews and family photos to tell the story.

Editing: You can increase the production value and sustain viewer engagement by diversifying and enriching the content with creative editing. Editing is an art but is easily learned with relatively inexpensive or free software. And because you’ve already viewed hundreds of thousands of hours of professionally edited film and video on television, you probably already have an inherent feel for proper pacing.

Timing and effects: every scene should be timed so a slower-than-average viewer can comfortably scan the screen, track movement, and absorb the meaning of it. Useful effects include displaying text at normal reading speed with a typewriter-style reveal; editing interviews with slow talkers to eliminate unnatural pauses; and subtitling fast-talkers or heavily accented speakers.

Illustrated Print

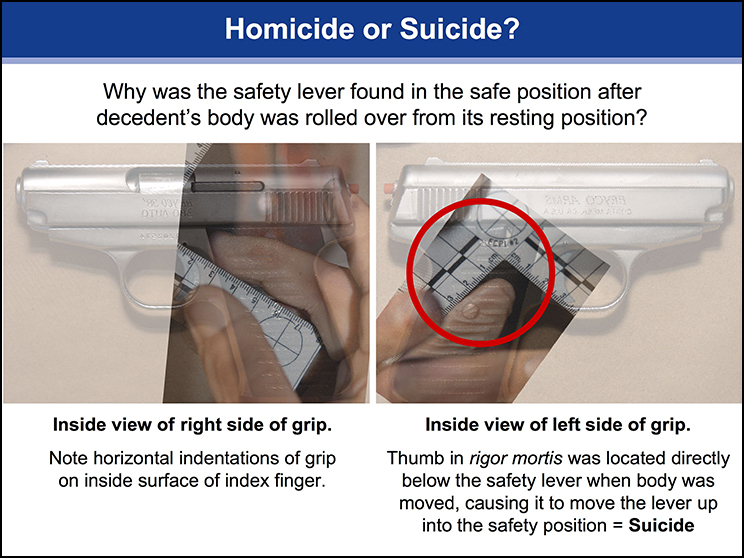

Digital or hard copy print is the easiest media to produce, reproduce, distribute, view, and file. And there are some courts and prosecutors who accept nothing else. But that doesn’t mean visuals are excluded. Print is the natural medium for presenting crucial documentary evidence and reports by psychosocial mitigation specialists and mental health evaluators.

Easily embedded into text or attached as exhibits, visual content can emphasize or replace written information. It can comprise medical, technical, or editorial illustrations and photographs, video or animation still frames, charts, maps and diagrams. And we’re all familiar with hyperlinks to external media.

For video content, you might establish a secure online YouTube or Vimeo account for archived password-protected video content only your viewers can access.

Conclusion

Bringing the human side of your client’s story to life is the ultimate goal and visual persuasion accomplishes that, perhaps better than a conventional written submission. And if you fail to get the case dismissed or the charge reduced, your effort won’t be wasted if content is repurposed in later procedures.

As such, visual persuasion aids the accused and convicted many ways—and is limited only by your imagination. So, be creative!