A Lesson from the Derek Chauvin Trial: Don’t Miss an Opportunity to Persuade Visually

Lay jurors appreciate visual aids to enable full understanding of the evidence and expert opinions. This is common sense, right?

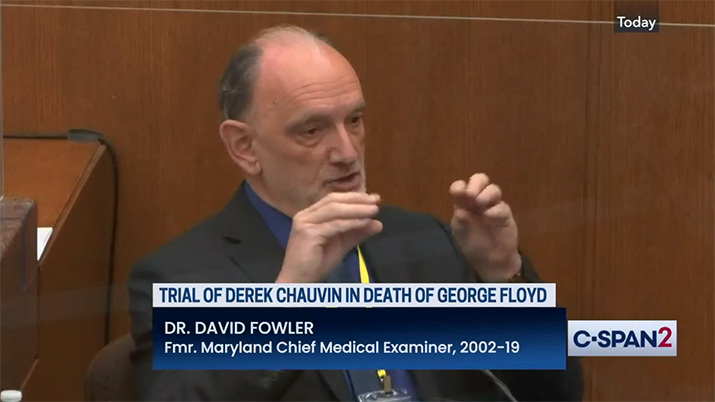

For example, imagine listening to an expert’s lengthy and highly technical explanation about the electrophysiological structure and operation in the heart, the location and function of the cardiac arteries, and tying that to the mechanism of death. Imagine doing so without the benefit of visual aids, and you get an idea what the Derek Chauvin-George Floyd death trial jury endured.

Anecdotally, a pool reporter monitoring the trial reported the jury was fidgeting during the lengthy testimony of defense medical expert David Fowler, M.D., a highly experienced former chief medical examiner for the State of Maryland and private forensic consultant. Jurors were purportedly looking around and stretching, apparently distracted or bored.

Although in this case it is impossible to know for sure, it is similar to a situation in which the perception of need for demonstrative exhibits is left to an expert so confident words alone are sufficient and/or an attorney who is convinced the expert’s oral persuasion renders the benefit of visualizing physical descriptions unnecessary.

Because jurors cannot ask for clarification during oral testimony, trial lawyers must anticipate potential juror tolerance for technical testimony, confusion, and bewilderment. Even judges are not immune (although they can request elaboration). The late Hon. Rudi Brewster, former Senior Judge of the Southern District of California admitted,

“I have a real problem with some technology. I never had high school chemistry, and I have a real ‘hole in my head’ when it comes to that kind of technology…. If I can’t explain the technology successfully to my 12-year-old granddaughter, I know I don’t understand the technology fully myself.”[1]

Whose perception of need is paramount?

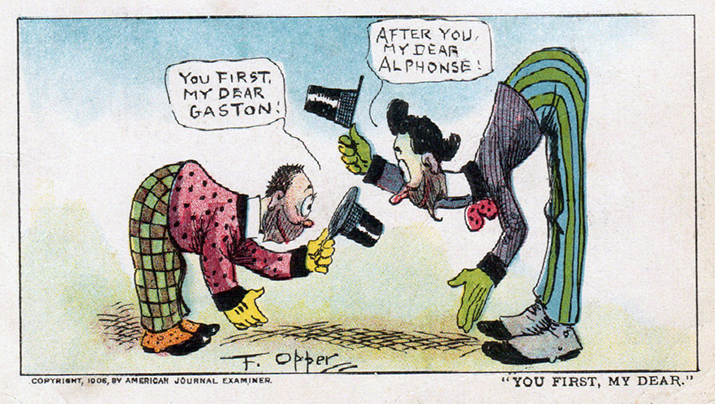

In my experience, a curious “turf” issue can arise regarding respective attorney and expert perceptions of need for demonstrative exhibits benefitting the finders of fact.

Because experts are generally tasked with formulating the best way to explain a topic and the manner it is presented, a lawyer might defer to the expert to conceive any demonstrative exhibits she perceives are necessary to accomplish that task.

And because attorneys control the scope and pacing of testimony, and ascertain what the neutrals should hear and see, an expert might rely on the lawyer to suggest demonstrative exhibits he perceives will benefit learners.

A state of stasis occurs when neither expert nor lawyer infringes the other’s presumed turf. In such a situation how will a future perceived need by fact finders be satisfied? As illustrated in the Chauvin trial, it might not.

Third party advocates for fact finders can break the logjam. Trial/jury consultants and graphics consultants proactively fulfill this role. The themes “what will the jury think?,” “what does the jury need?,” and “how will the jury perceive this” drive our collective efforts.

We will suggest deploying visual communication when the learner benefits and oral delivery alone is inadequate. Thus, while the lawyer’s or the expert’s personal preference can be influential, it is largely irrelevant if the learner’s needs for visual aids are greater.

70 years of visual advocacy

Some experts and trial lawyers are excellent visual thinkers and teachers. Melvin Belli wrote “Modern Trials” in 1954, advocating for, and providing dozens of examples of, persuasive demonstrative exhibits (not limited to the visual realm) he and others used by that time.

When I entered the field in the mid-1970s, my first clients advocated visual teaching, even while some derided visual aids as props for lousy lawyers. Today, we might assume most people are visual learners given our culture’s visually immersive nature, and visual aids in litigation are ubiquitous.

But, as the Chauvin trial exposed, there is room for improvement.

Be proactive about visual advocacy

As much as the defense in Chauvin might have missed opportunities to persuade visually, the prosecution rarely did. Some notable examples:

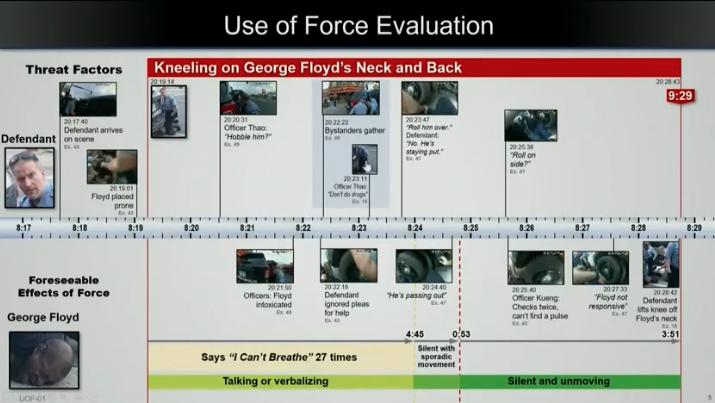

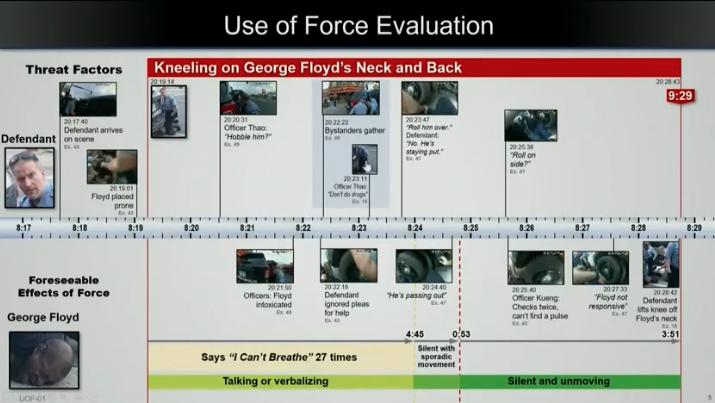

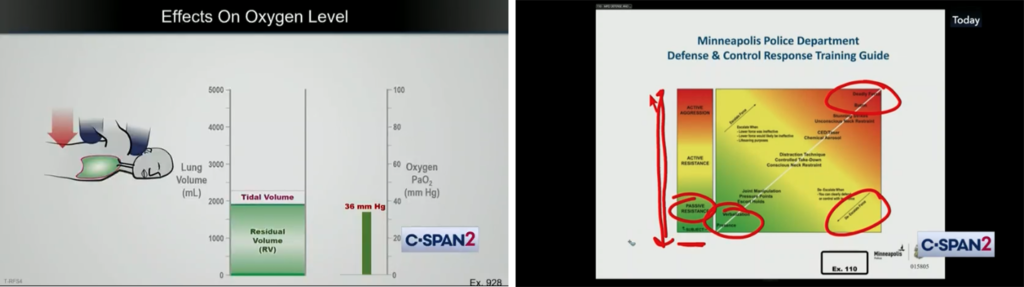

- An interactive timeline documenting milestone events of Mr. Floyd’s gradual decline from vigorous agitation to death

- Medical illustrations and graphs explaining the correlation between pressure, airway dimension, oxygen depletion, and death

- Eyewitness and body-worn-camera points of view demonstrating participant awareness of Mr. Floyd’s condition

- Documentation of police training pertaining to use of force to subdue a resisting suspect

While the quantity of demonstratives presented is meaningless, clearly the prosecution’s consistent use of visual communication was designed for the jury’s benefit.What you can do.Put yourself in the seat of an influencer (e.g., mediator) or decision maker unfamiliar with the subject, location, customs, or mechanics of a topic, and ask, “what should I know to do my job?”Challenge yourself and your experts to think visually. If you’re stymied, seek the advice of a trial or graphics consultant.

Be mindful how the benefit of visual communication might extend beyond pure education. Intense concentration on highly technical information is fatiguing. Visual stimuli help learners sustain focus and retain crucial information.

Endnote:

[1] Seminar on Trying Patent Cases, San Diego Intellectual Property Law Association, California Western School of Law, March 1, 2006