How to Sell Your Construction Defect Outcome with Visual Proof

Is judging a construction defect always a binary decision between deciding right vs. wrong, or proper vs. improper? That depends on how you frame the question. Besides blatant code violations or outright failures, whether a suspected condition is defective might be an interpretation that visual evidence can tip one way or the other.

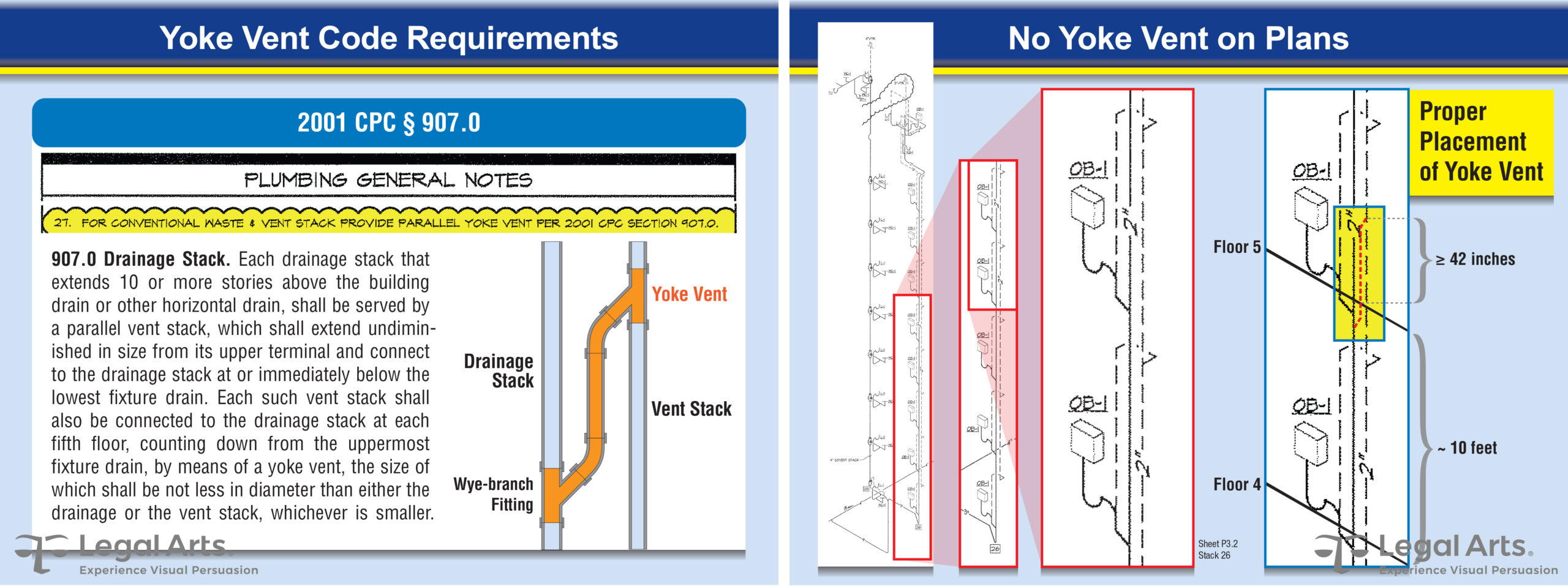

For example, the plaintiff’s expert in a mid-rise condominium tower defect case used code and plan specification language to promote a pass-fail performance standard for installing yoke vents in a mid-rise condominium tower’s waste-vent stacks. Either the vents were properly installed every 5 floors if the stacks exceeded 10 floors, or they weren’t. If not, was this “case closed”? [1]

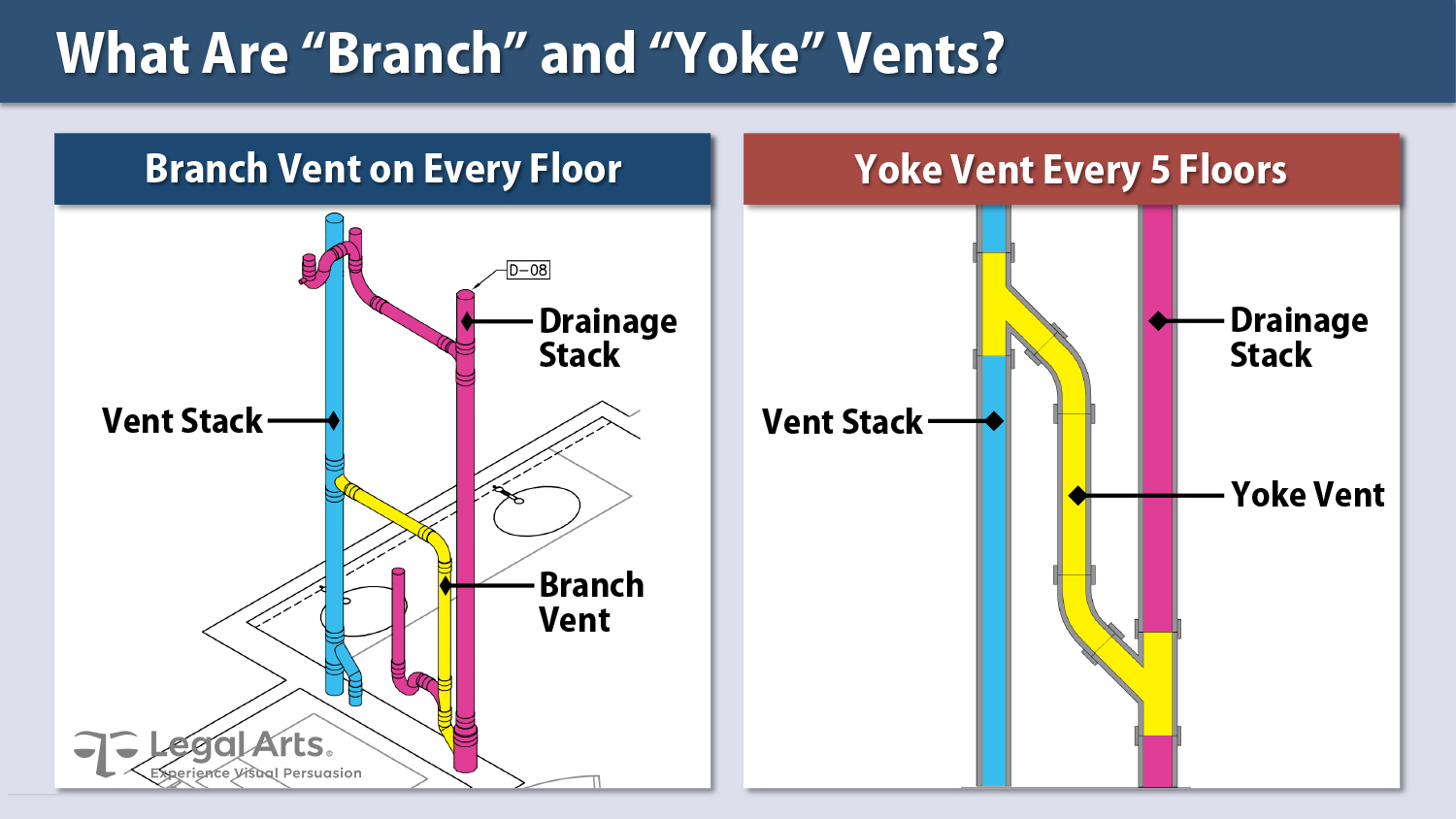

If so, consider this high-rise tower matter in which the defense demonstrated how a design workaround called a branch vent installed on every floor performed better than a single yoke vent installed every 5 floors:

The defendant’s branch vent design workaround comparison to a conventional yoke vent solution demonstrates how performance, rather than a single Code-compliant design, should determine the proper outcome. To reinforce this point, counsel also commissioned an animation demonstrating how the alternative design vented air from the system. Is this case now closed? [2]

There are several creative approaches to building a visual frame of reference and forging a desirable outcome.

Proper vs. Improper Design and/or Construction

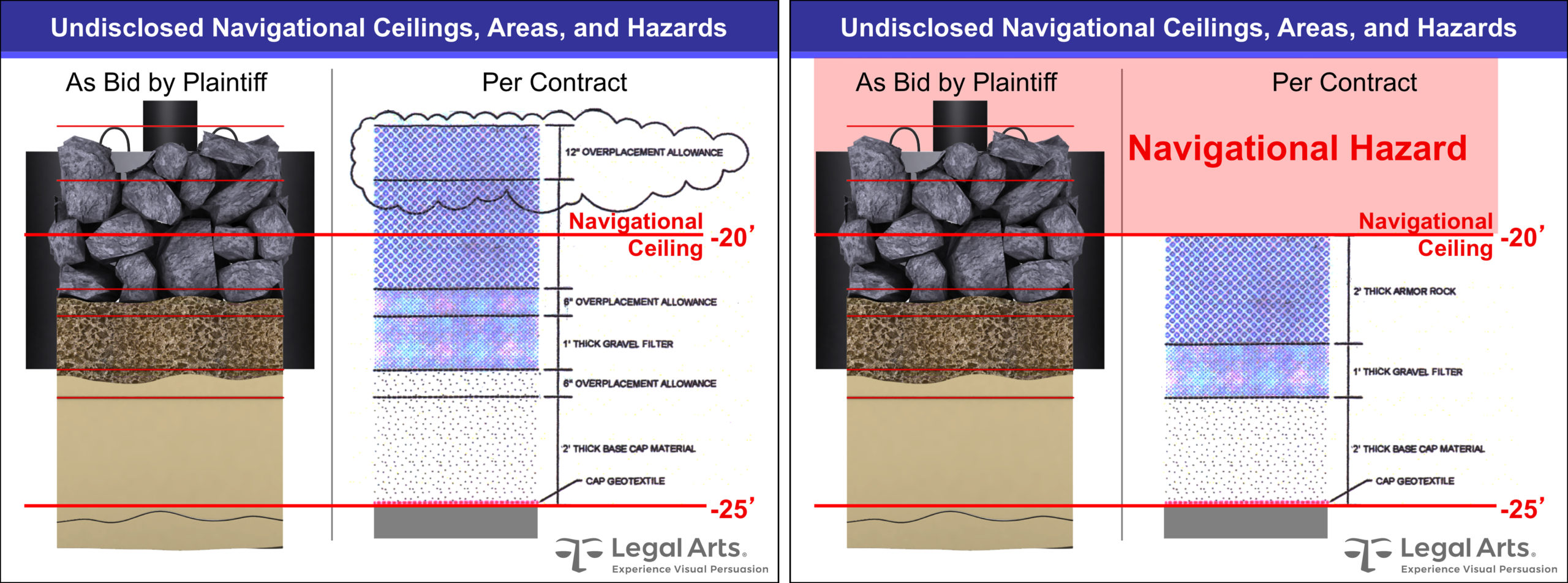

In this marine construction dispute, the plaintiff contractor sought to recover unpaid costs related to the demolition and removal of existing structures and debris, dredging and disposal of contaminated sediment, and installing an engineered cap system.

The contractor claimed the defendant Port was liable for extra costs because its contract documents were ambiguous. A visual example of this, which would have resulted in constructing a navigational hazard if built to plan, demonstrated why the plaintiff was forced to spend extra time and money engineering safe workarounds:

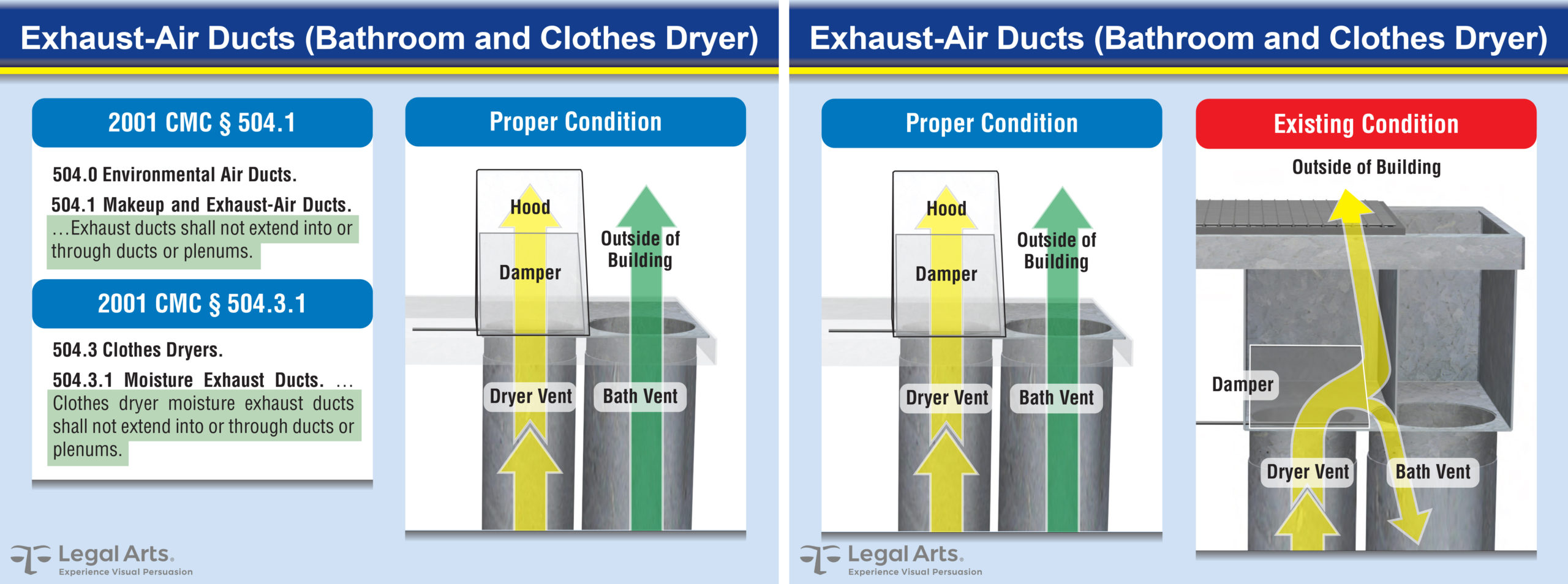

To demonstrate how dual exhaust-air ducts should direct air outside a building, an illustration paired with Code language is persuasive. When compared to the alleged defective condition featuring a prohibited plenum, or enclosed space, between the end of the ducts and the outside, we can see how exhaust backdraft from the dryer might enter the bath vent and cause excessive moisture buildup in the bathroom:

Combining Code language with an illustration of “proper” construction reinforces the concept—correctly or not—there is oneright way to comply with the rules of the road. Similarly, demonstrating the cause and effect of “proper” and “improper” conditions creates an indelible takeaway that a negative outcome is a direct consequence of the designer choosing not to comply with the rules.

Visually teaching neutrals (and stakeholders) the “right way” to design or construct something, or which materials should be used, can establish a reasonable benchmark to evaluate the accused construction.

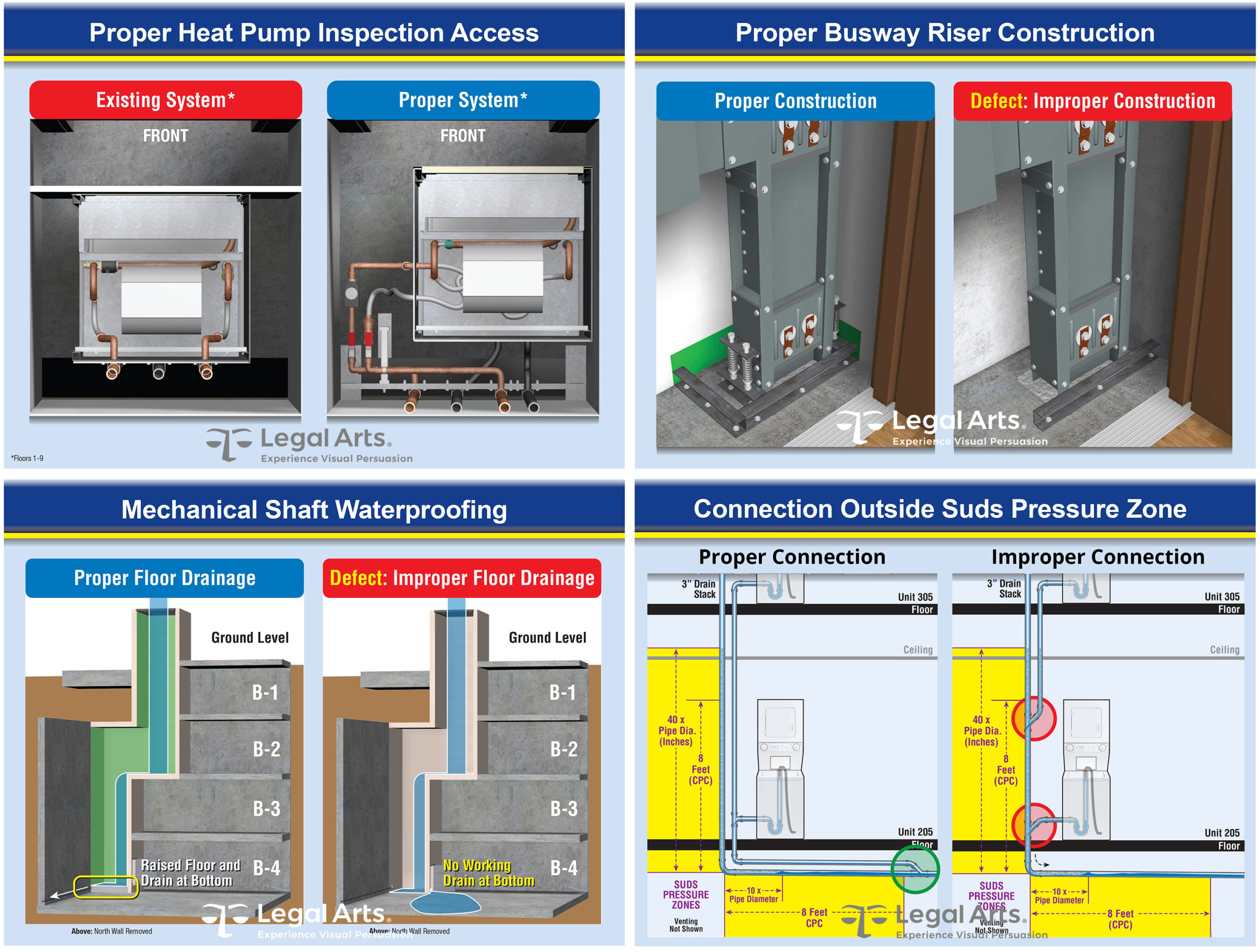

In the mid-rise tower case, establishing the “proper” context was a consistent plaintiff theme for multiple claimed defects:

Conversely, demonstrating a reasonable performance workaround was a legitimate defense theme in the high-rise tower case.

Proper vs. Improper Visualization

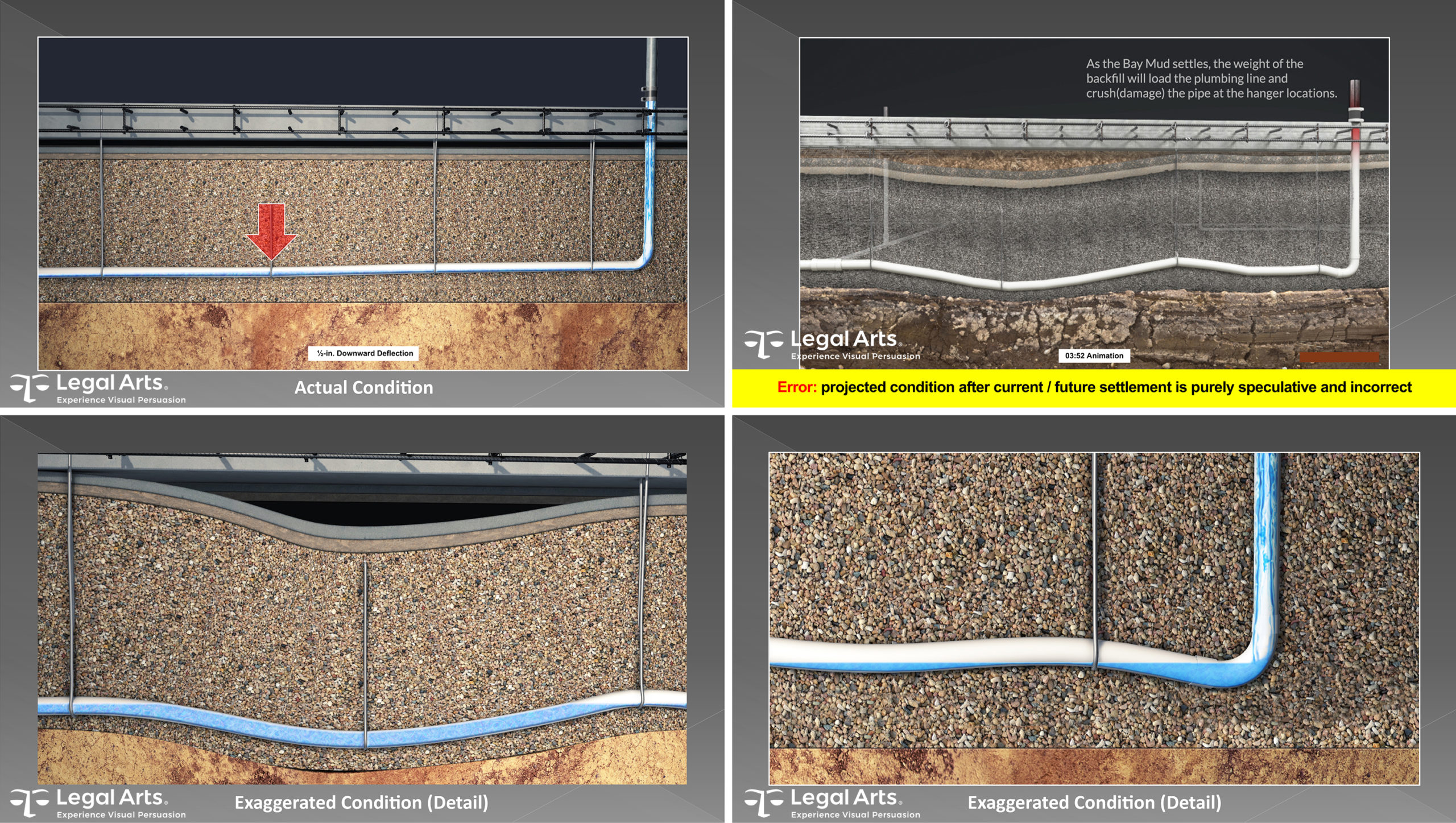

To be convincing, demonstrative exhibits have to be accurate. In this bellwether case involving underground piping in bayfront soil prone to uniform post-construction settlement, the plaintiff commissioned highly realistic 3D-animations to demonstrate the purported future damage that pipe sections between hanger locations would inevitably experience.

This inaccurate “wet noodle” animation grossly exaggerated documented pipe damage and misrepresented soil settlement mechanics. For example, the soil inexplicably settles only between intact hanger locations as if the thin wires hold both the pipe and the surrounding soil in place:

This likely very expensive advocacy tutorial had zero impact on settlement value because it was so inaccurate the defense would have had little problem preventing its publication to a jury, or if unopposed, would cast serious doubt about the truthfulness of the plaintiffs’ case.

Visually Quantifying Defects

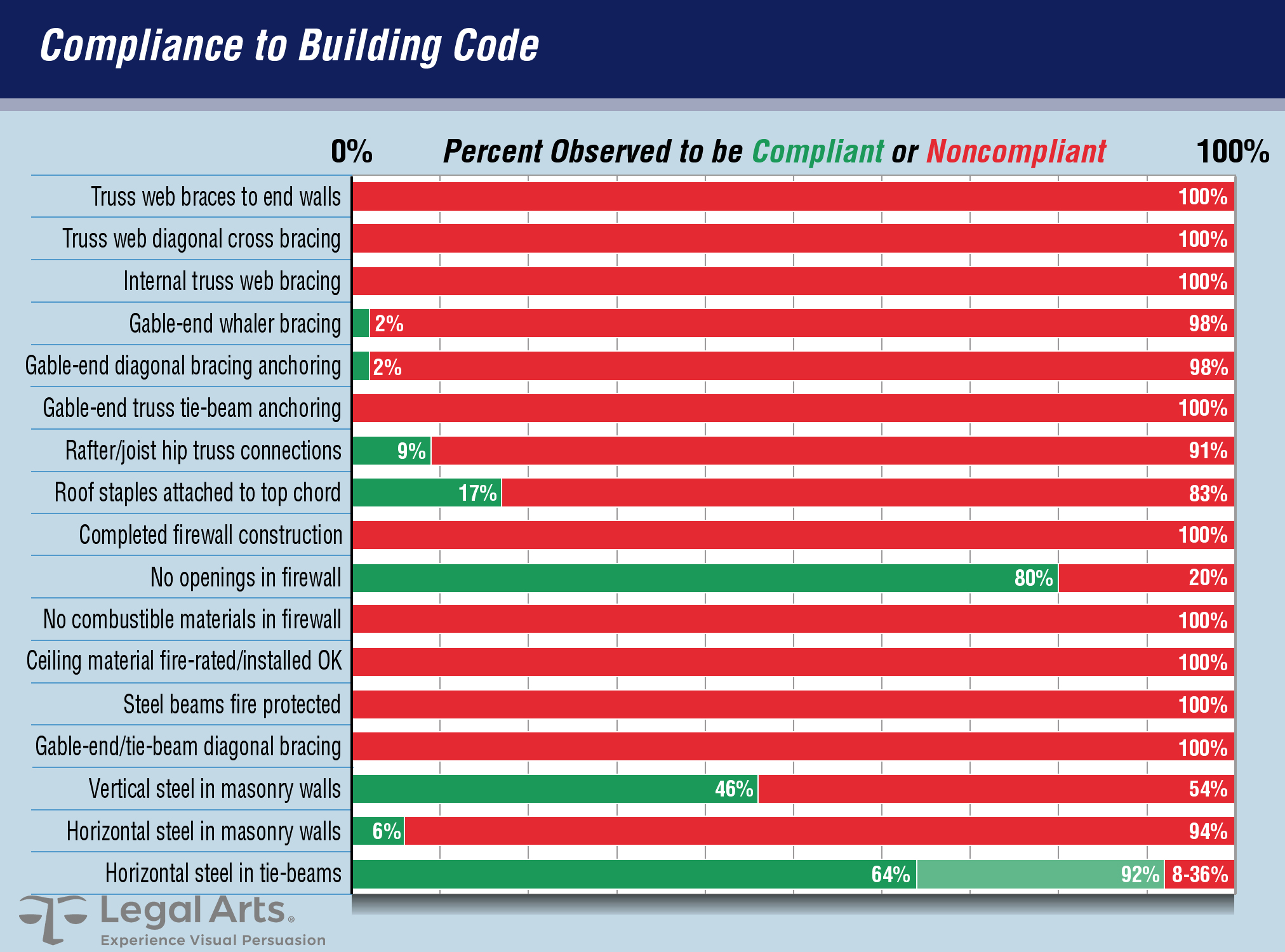

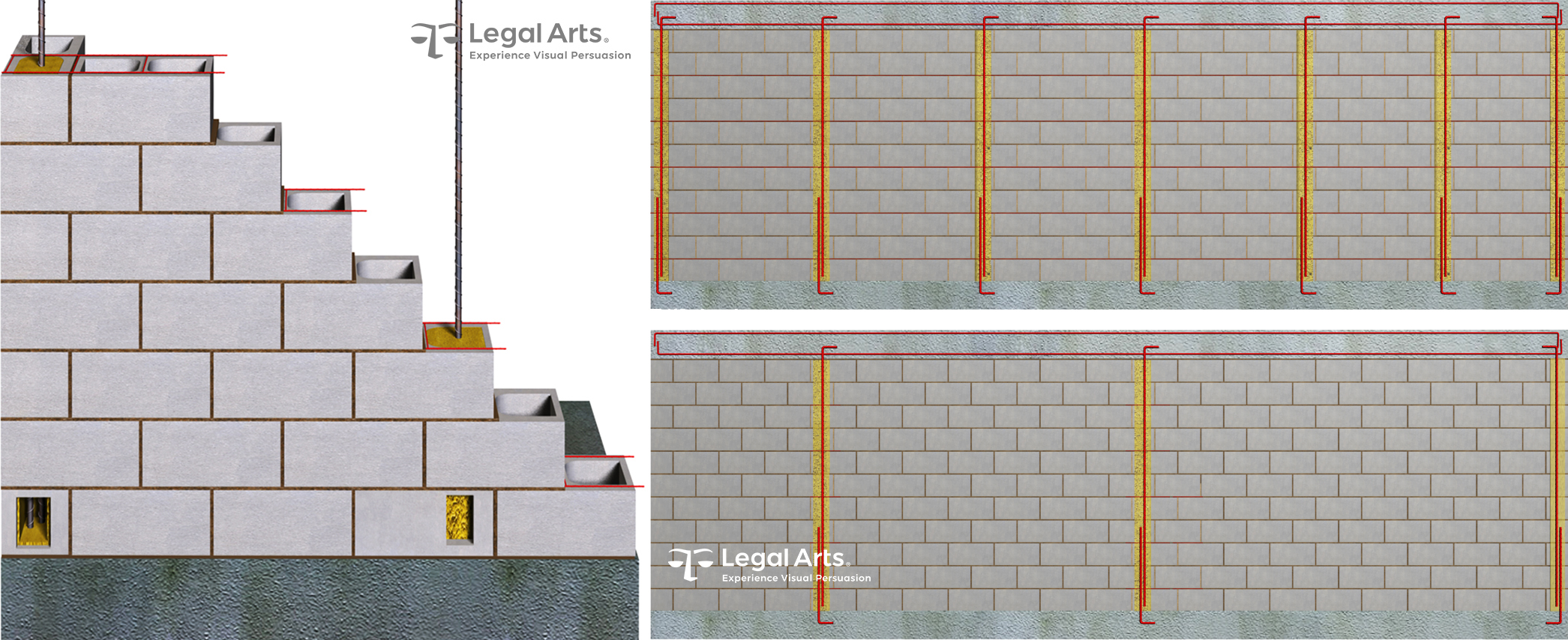

The approach in this next case was quantifying over a dozen categories of construction and material defects. Inspections of over a hundred four-plex units in the plaintiffs’ Miami development uncovered serious Code violations making the properties so vulnerable to damage from Category-3 or higher hurricanes that the Court condemned them all.

To illustrate the locations and extent of the defects in a typical unit, we created an interactive presentation enabling the presenter to selectively display 14 construction components or materials alone or in any combination with others in the structure. The presenter could build the structure from the slab up or roof down, or isolate certain materials such as the structural steel, as this composite animation demonstrates:

Missing steel in the concrete block walls was the most serious defect because it is vitally important to maintaining structural integrity from the lateral forces exerted on walls during a hurricane. Destructive and radiological testing revealed 54% of the vertical steel and 94% of the horizontal steel was missing from the concrete block walls. These illustrations demonstrate to-Code compliance (left and top right) and the as-built condition of a typical wall (bottom right). [3]

In the high-rise condominium tower case cited above, plaintiffs’ proposed remedy was removal of miles of suspected Chinese cast iron drain and vent pipe and replacement with domestic pipe.

In the high-rise condominium tower case cited above, plaintiffs’ proposed remedy was removal of miles of supposedly defective Chinese cast iron drain and vent pipe and replacement with domestic pipe.

We prepared this animation illustrating the 23 cast iron waste-vent stacks to demonstrate the physical scope of this issue.

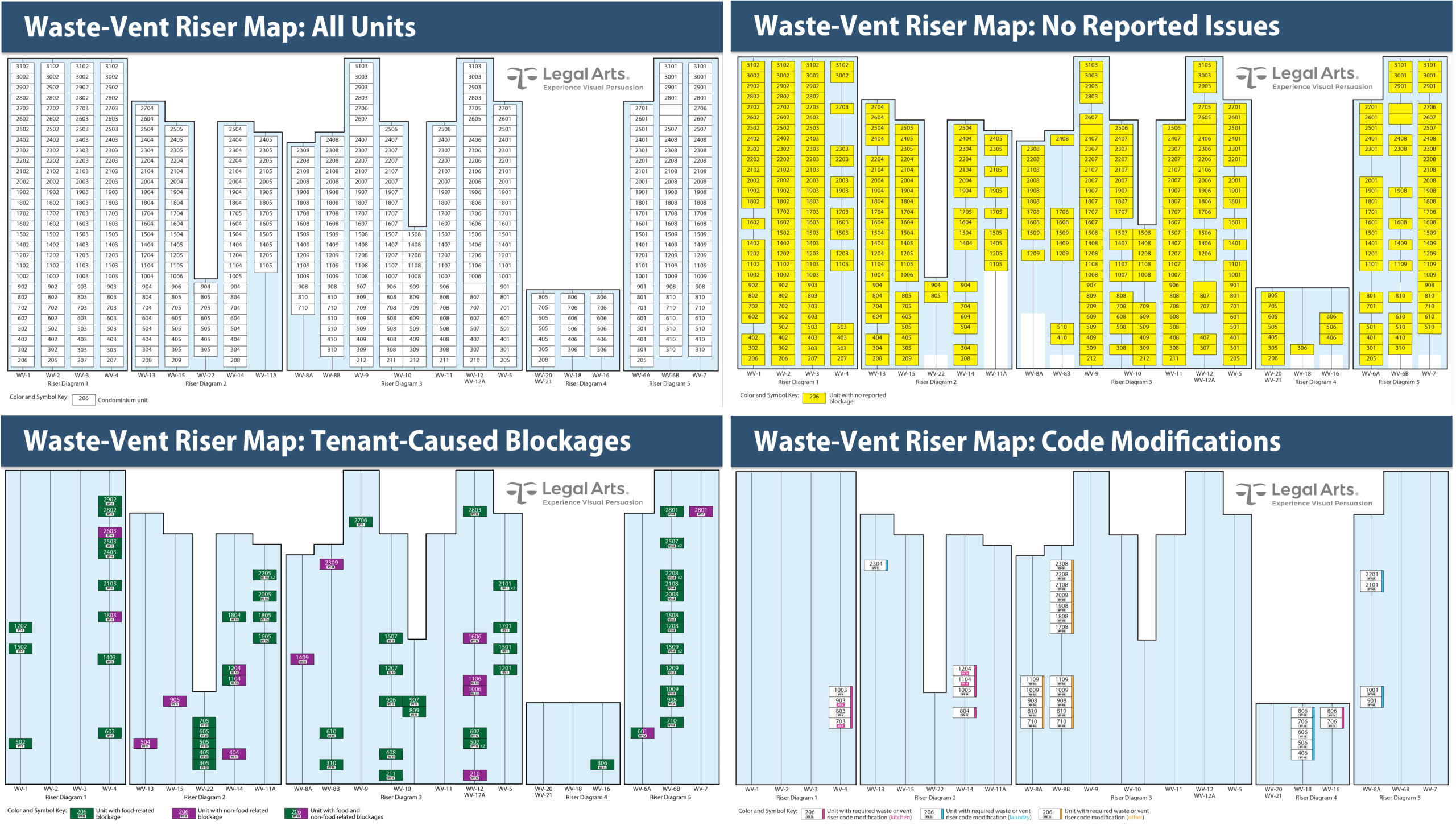

The defense believed this proposed remedy was overkill given the relatively limited construction-related problems experienced during the first seven years in the life of the building. We quantified the number of construction-related defects in the series below. In the upper left graphic each waste-vent stack is represented by a stack of white tiles representing the condominiums it affects.

In all there are 480 waste-vent-interactions. Of these, 381 (79%) were unaffected by any problems (depicted in yellow in the upper right image) and 65 (13.5%) experienced only tenant-caused blockages (lower left), leaving just 37 (7.7%) with code modification issues in just 8 (35%) of the stacks (lower right).

We can also quantify detrimental effects with data graphics and either emphasize or deemphasize the perceived impact using different data visualization methods.

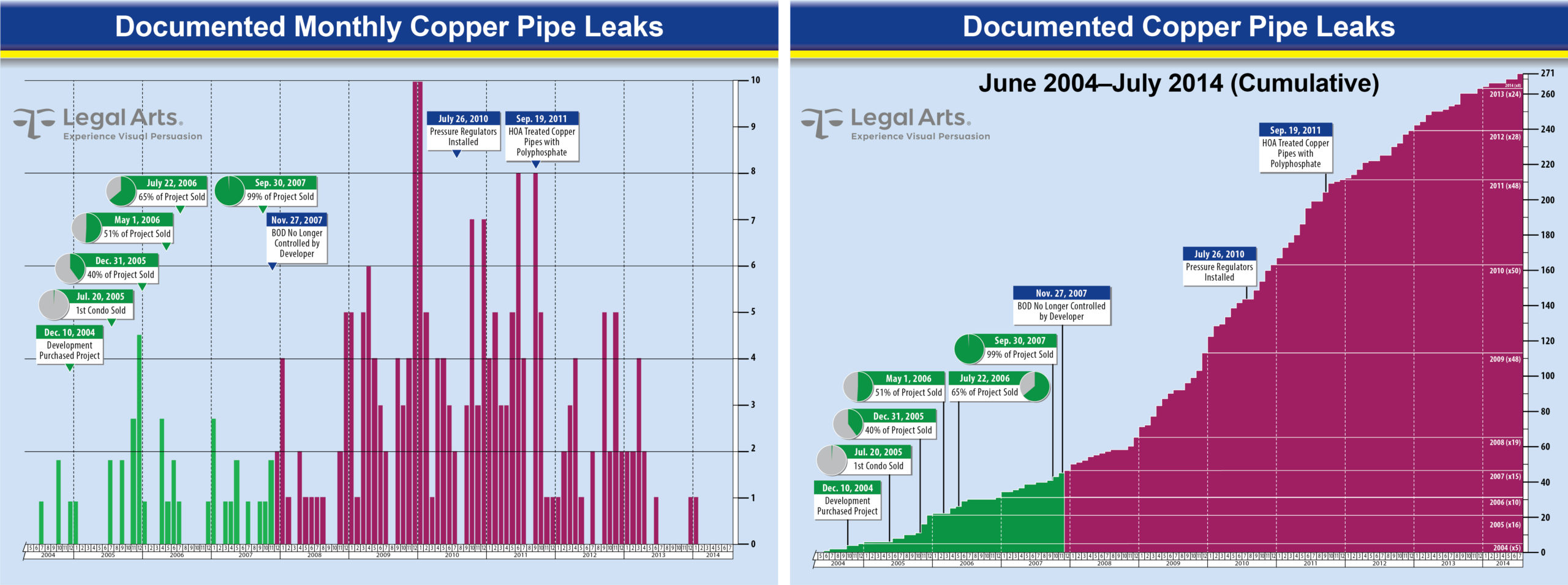

In this case, the owners of a decade-old 500+ unit condominium project responded to almost 300 copper pipe leaks over the life of the property. While leakage was continuous, the frequency of calls fell during later years.

Plaintiffs’ counsel was concerned that a conventional monthly visualization of calls would demonstrate the problems were diminishing if not mostly resolved 10 years after they started (upper left).

Instead, they wanted to demonstrate the root cause of the leaks was a problem that would never go away and without widespread replacement, would never resolve on its own. By changing the data visualization from monthly to a cumulative “mountain” of problems (upper right), the frame of reference was changed to support the plaintiffs’ position.

Creative tips for counsel:

- Comparisons are a popular way to create a compelling frame of reference for the outcome you seek

- A reliable plaintiff’s theme is demonstrating proper versus improper Code compliance

- A persuasive defense theme is demonstrating performance workarounds that achieve the same outcome as the plaintiff’s proposed remedies

- Comparisons are an efficient and persuasive method of establishing, reinforcing, or mitigating emotional takeaways to influence decision making (e.g., “that isn’t right,” “they should’ve known better,” “there’s more than one way”)

- Because construction defect cases rarely go to trial, putting your most persuasive case forward in ADR might be the most cost-effective decision you can make

- Tutorials will help the stakeholders, influencers, and fact finders interpret the standards ruling proper design and construction

- Manipulating data visualization is potentially risky because you might be accused of “lying with charts;” therefore, balance your objectives with how and when you intend to display manipulated data very carefully (e.g., mediation versus trial)[4]

Endnotes

[1] This mid-rise tower case study is available for download online at https://legalarts.com/case-study/mid-rise-condo-tower-construction-defect/

[2] This high-rise tower case study is available for download online at https://legalarts.com/case-study/construction-defect-high-rise-condominium-tower-plumbing-hvac-and-windows/

[3] This hurricane-county case study is available for download online at https://legalarts.com/case-study/construction-defect-miami-hurricane/

[4] See https://legalarts.com/visual-persuasion-blog/data-visualization-rules/

© 2020, Legal Arts, Inc.