Gain the Upper Hand by Visualizing Your Trade Secret Case

Proving of disproving trade secret misappropriation in intellectual property, employment, and industrial espionage cases is prime opportunity for visually demonstrating motive, opportunity, access, pattern of behavior, and protection mechanisms (or the lack thereof).

This collection of demonstratives from several Legal Arts matters illustrates how you can gain a visual advantage when litigating plaintiff and defense counsel civil trade secret misappropriation.

The non-secret

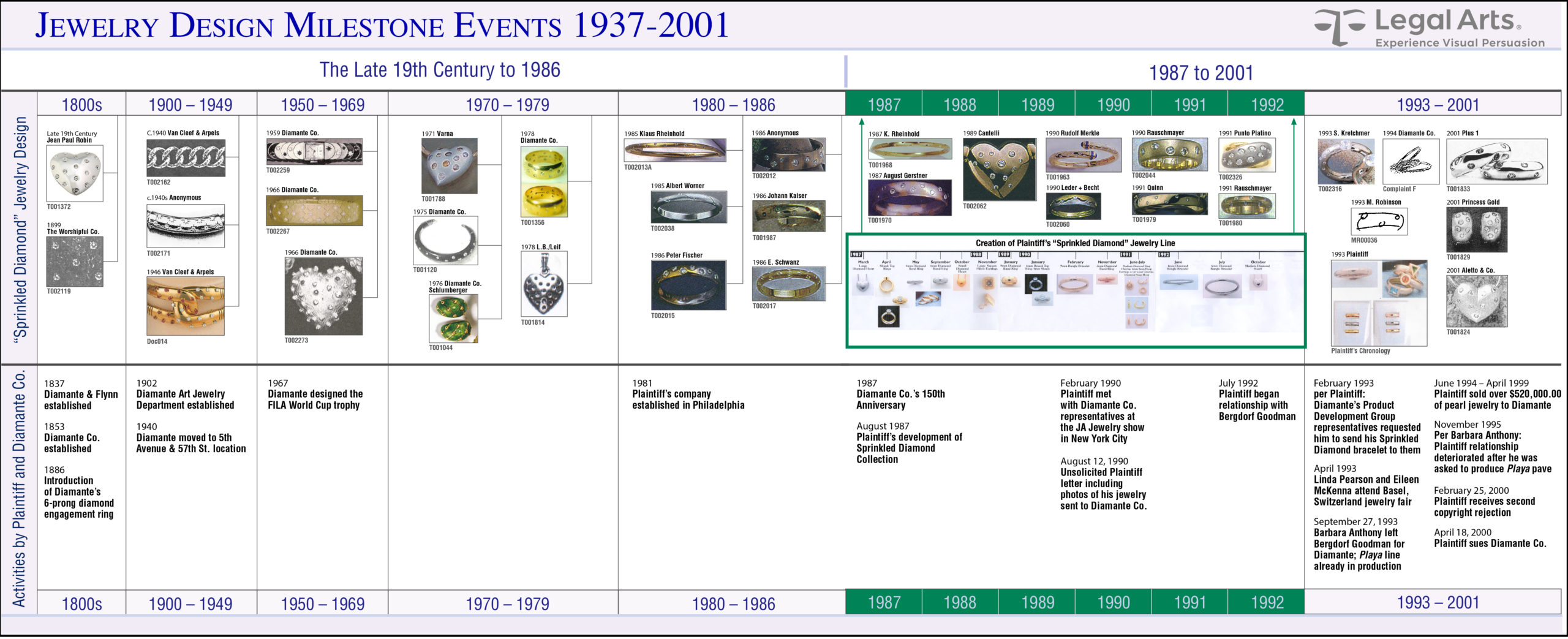

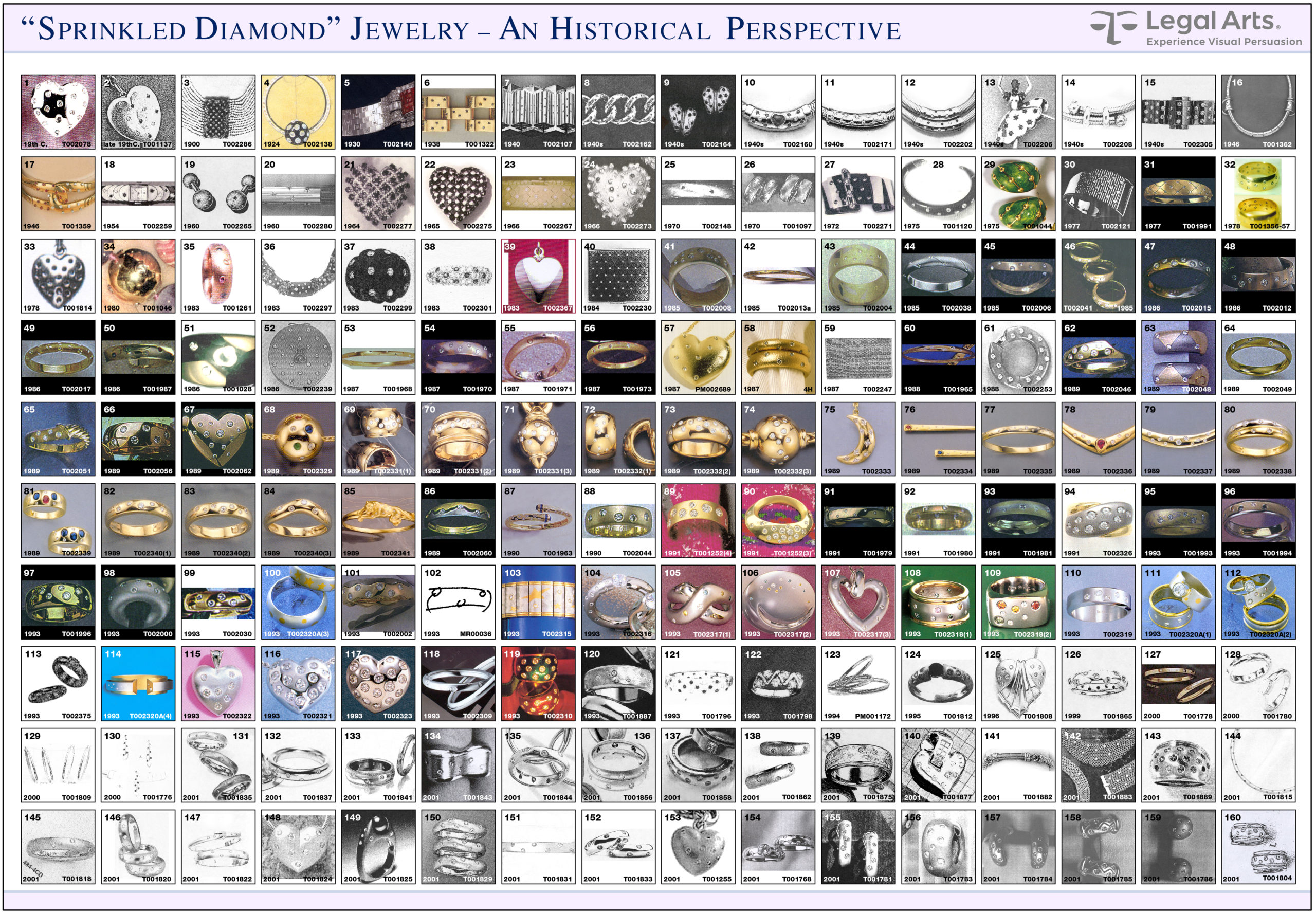

In a trade secret misappropriation and copyright infringement matter tried in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, the plaintiff jeweler proposed selling a supposedly proprietary line of relatively affordable “sprinkled diamond” designs to the defendant, a world-renowned jeweler, which declined. To the plaintiff’s chagrin, the defendant later launched a new line of rings, bracelets, pendants, and necklaces he believed copied his rejected design.

The plaintiff sued for trade secret misappropriation and copyright infringement. In trial, the defense produced evidence of similar jewelry designs dating to the late 19th Century, including its own products from the 1950s through the 1970s, and dozens of contemporary examples by European jewelers. This timeline documented several design milestone events:

To demonstrate the immense popularity of geometric spacing of small jewels on metal and why the plaintiff’s jewelry design was not unique or distinctive, we prepared a photographic matrix of 160 pieces demonstrating similar designs to the plaintiff’s disclosed products:

The jury agreed, delivering a complete defense verdict and finding none of the plaintiff’s designs to be copyrightable.

This case is also featured in Case Studies at https://legalarts.com/case-study/copyright-infringement-jewelry-designs/

Creative tips for counsel:

- Extensive investigation might be necessary to find relevant prior art; our primary sources for this case were the defendant’s library of competitor catalogues and international trade publications

- How you present temporal context can shape fact finder takeaways; every event in your protected and/or accused product development chronology should relate directly to the knowledge or opportunity of knowing the prior art

Independent creation

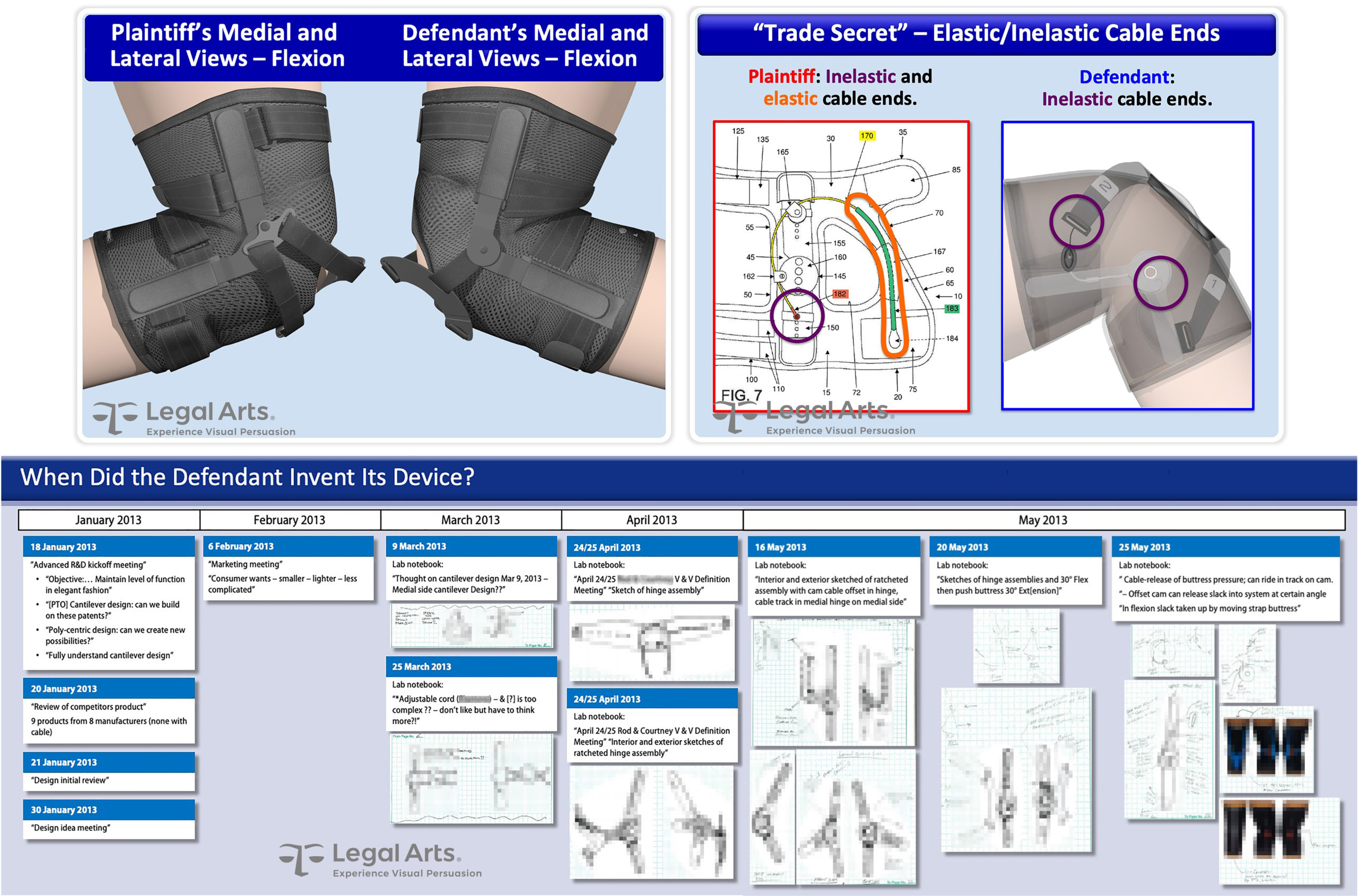

After the plaintiff’s proposal to sell his therapeutic knee brace design to the defendant sports medicine device maker fell through, he accused the defendant of incorporating key features of his design (patented after their meeting) in one of their best-selling products.

The accused product’s mechanical operation appeared similar but comprised key differences. Regardless, the primary defense was independent if not simultaneous invention, and the most convincing documentary evidence was the defendant’s engineering lab workbooks, which told the origination story from before the plaintiff’s proposal through prototyping and production. The case settled before trial.

Creative tips for counsel:

- Prepare a technology tutorial to teach your audience all they’ll need to understand about the basic mechanical concepts germane to the secrets at issue

- Test your graphics to confirm you impart the right takeaway; for example, overlaying two products to demonstrate 90% similarity might instead emphasize the 10% difference

- Corroborating evidence like the lab workbooks or deposition testimony can break a he-said/he-said stalemate

Alternative inspiration

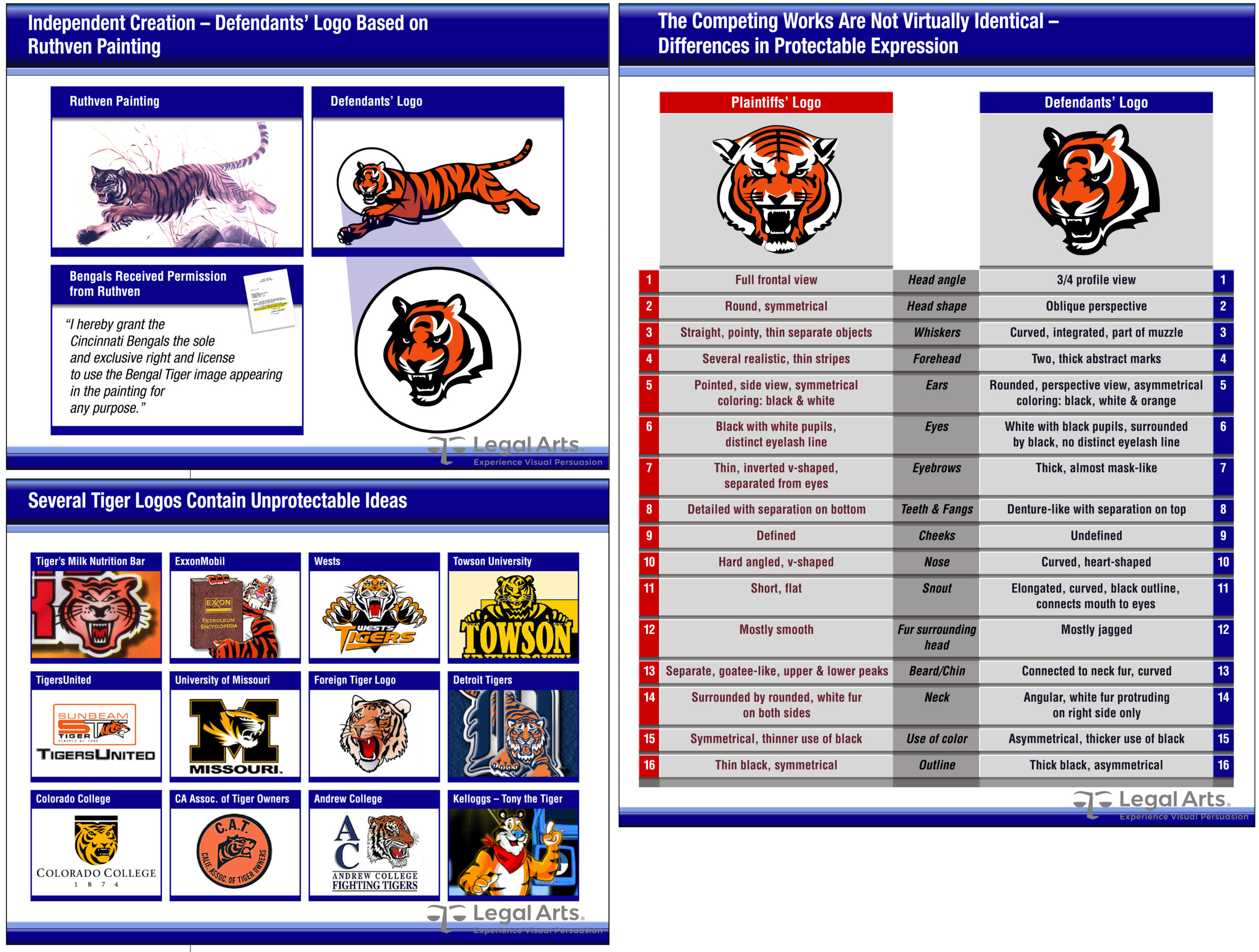

In another case of an unsolicited disclosure by the plaintiff, the defendant NFL football club was accused of misappropriating a tiger face design for its trademarks.

The three-pronged defense was (a) demonstrable differences in protectable expression; (b) similarities of the plaintiff’s design to unprotectable ideas; and (c) independent creation based an alternative source for which the artist assigned an exclusive right and license to the defendant.

The Court ruled in the defendant’s favor on several dispositive motions and the remaining claim was settled after mediation. This case study also appears in our website, available at https://legalarts.com/case-study/nfl-team-logo-origin-dispute/

Creative tips for counsel:

- While busy summary graphics might be a chore to read, quantity by itself can communicate a favorable takeaway; the 15 differences in protectable expression gave the trier of fact ample reasons to find for the defendant

- Why show a dozen examples of unprotectable prior art? Repetition is a well acknowledged method to command attention and emphasize a single takeaway

Preserve market share

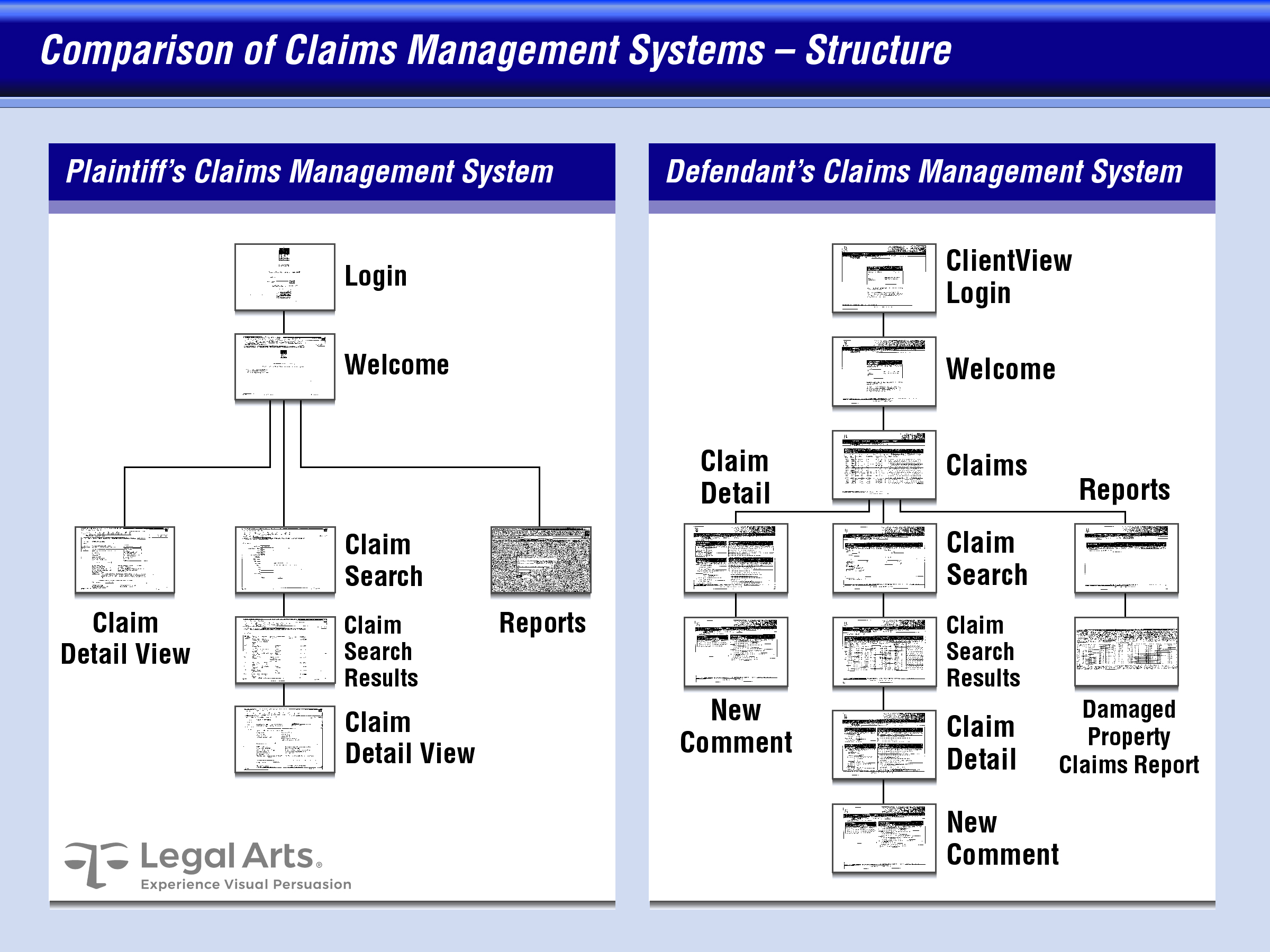

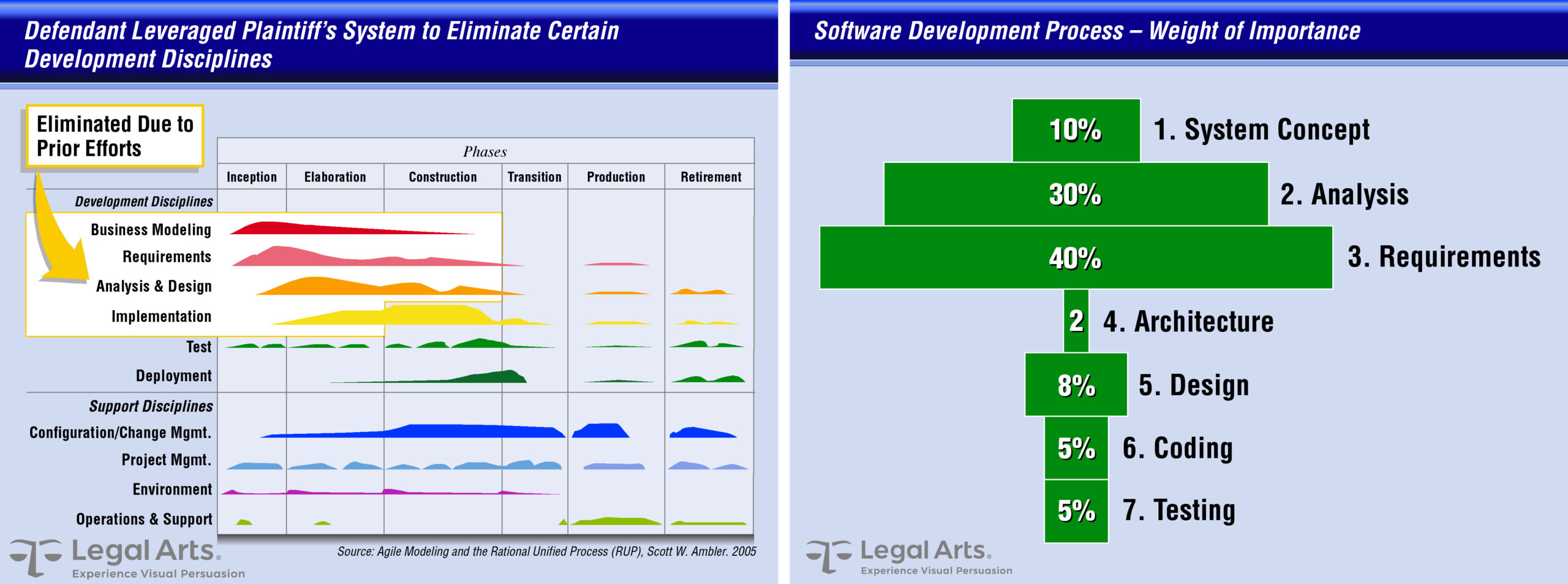

The defendant casualty insurance company was under enormous pressure to streamline its online claims process or face a significant loss of business. To motivate the plaintiff software developer to work around the clock to design and implement a new management system, the defendant tied compensation to the volume of claims adjusted using the application.

However, shortly after the successful launch of the new system the defendant abruptly cancelled the agreement and substituted an inferior internally designed replacement application modeled after the plaintiff’s product. The plaintiff sued the defendant for misappropriation of trade secrets and breach of contract.

We were engaged by the plaintiff to demonstrate the similarities of the two applications, explain the nuts and bolts of software development, apportion relative value to different stages of development, and to demonstrate how the defendant’s misappropriation robbed the plaintiff of most of the benefit of the bargain.

A key graphics source was the established modeling and process system used by the plaintiff to ensure fast, efficient, and reliable development of the desired application. This provided a suitable combination timeline, hierarchy, and labor intensity chart we adapted to demonstrate the portion of the development effort the defendant saved by misappropriating the plaintiff’s trade secret.

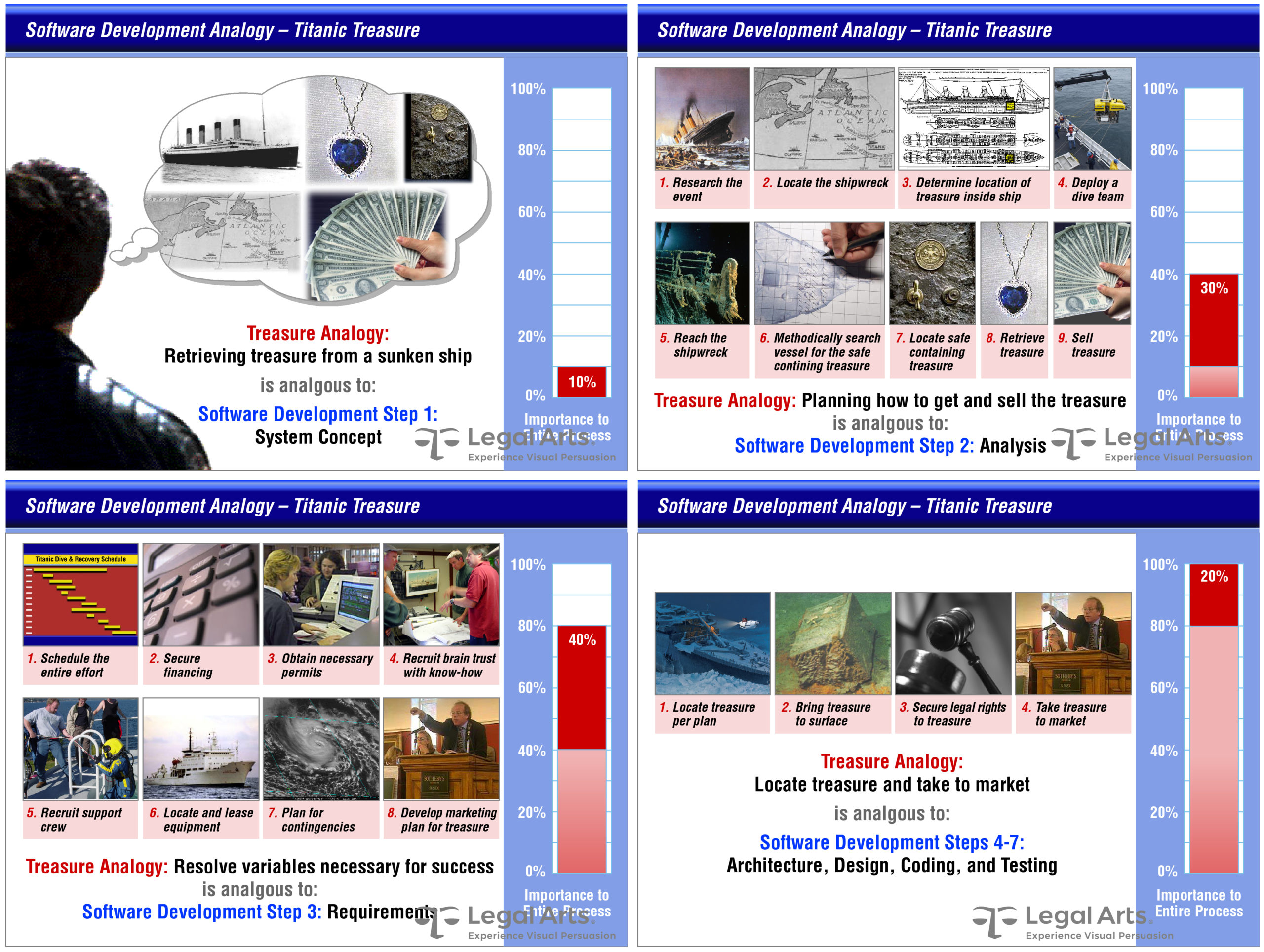

As clear as this solution was to software developers, we thought lay jurors might have trouble interpreting how this works in the real world. Counsel asked us to conceive a graphical analogy to demonstrate how the plaintiff’s efforts comprised most of the value of the product.

These graphics describe the immense effort of bringing sunken treasure from the Titanic to market as analogous to the different phases of software development:

Combining a compelling story and a progress gauge enabled the jury—we assumed most were familiar with the blockbuster Hollywood production “Titanic”—to make the connection. The strategy worked and the case settled just before trial.

Creative tips for counsel:

- Explaining misappropriation in some industries might require delving into esoteric subjects; establishing a familiar context directly or by analogy is a good way to start

- Saving considerable time and cost of trial-and-error experimentation to create a legitimate competitive product is a strong motivator to misappropriate trade secrets; demonstrate this by comparing the secret’s “roadmap” structure to the workaround

Visual and process analogies have great appeal, but they are fraught with potential pitfalls; play devil’s advocate and try to flip your analogy as you think your opponent might(for more information about using graphical analogies, see https://legalarts.com/visual-persuasion-blog/analogy-graphics/

Capture market share

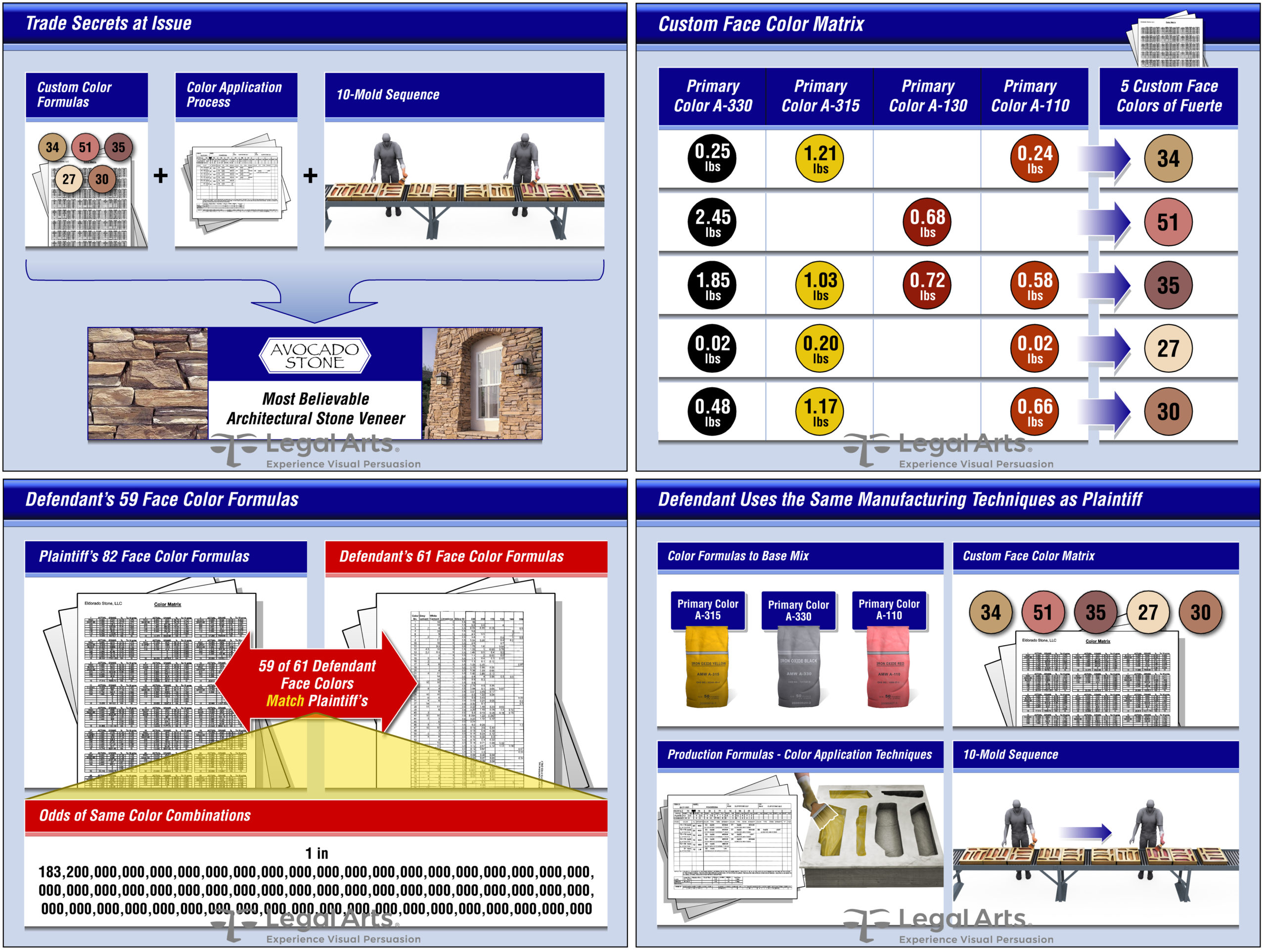

The defendant, an aspiring new player in manufactured architectural stone products, needed to build a large product line if he hoped to quickly penetrate the highly competitive niche market dominated locally by the plaintiff, his soon to be former employer.

Before quitting, the defendant copied his employer’s unique multiple-mold process, and to ensure the natural appearance and diversity of products, dozens of its proprietary color formulas.

Soon, the defendant was up and running, rapidly gaining—or stealing—valuable market share. Once the plaintiff closely examined their new competitor’s products, they believed the defendant had ripped them off.

We were engaged by plaintiff’s counsel to produce a manufacturing tutorial describing the trade secrets believed to be misappropriated. We also devised a way to demonstrate the astronomical odds of the defendant formulating 59 of 61 unique 5-component product colors without the knowledge of the plaintiff’s proprietary formulas.

The trial jury was convinced the defendant stole the trade secrets and used them in his competing products. They awarded over $20 million, including $4 million in punitive damages.

Learn more about this case study at https://legalarts.com/case-study/manufacturing-trade-secrets-misappropriation/

Creative tips for counsel:

- When the odds work in your favor, show the math by designing graphics that appeal to math-challenged individuals (please see https://legalarts.com/visual-persuasion-blog/math-challenged/)

- Tutorial graphics need not be fancy to be effective; consider using photos or videos to illustrate process steps and products (for this case we had to create illustrations for security reasons)

Build a better mousetrap

For major players, the need to constantly excel and sometimes to disrupt the marketplace is strong motivation to seek breakthrough technologies in every corner of the globe.

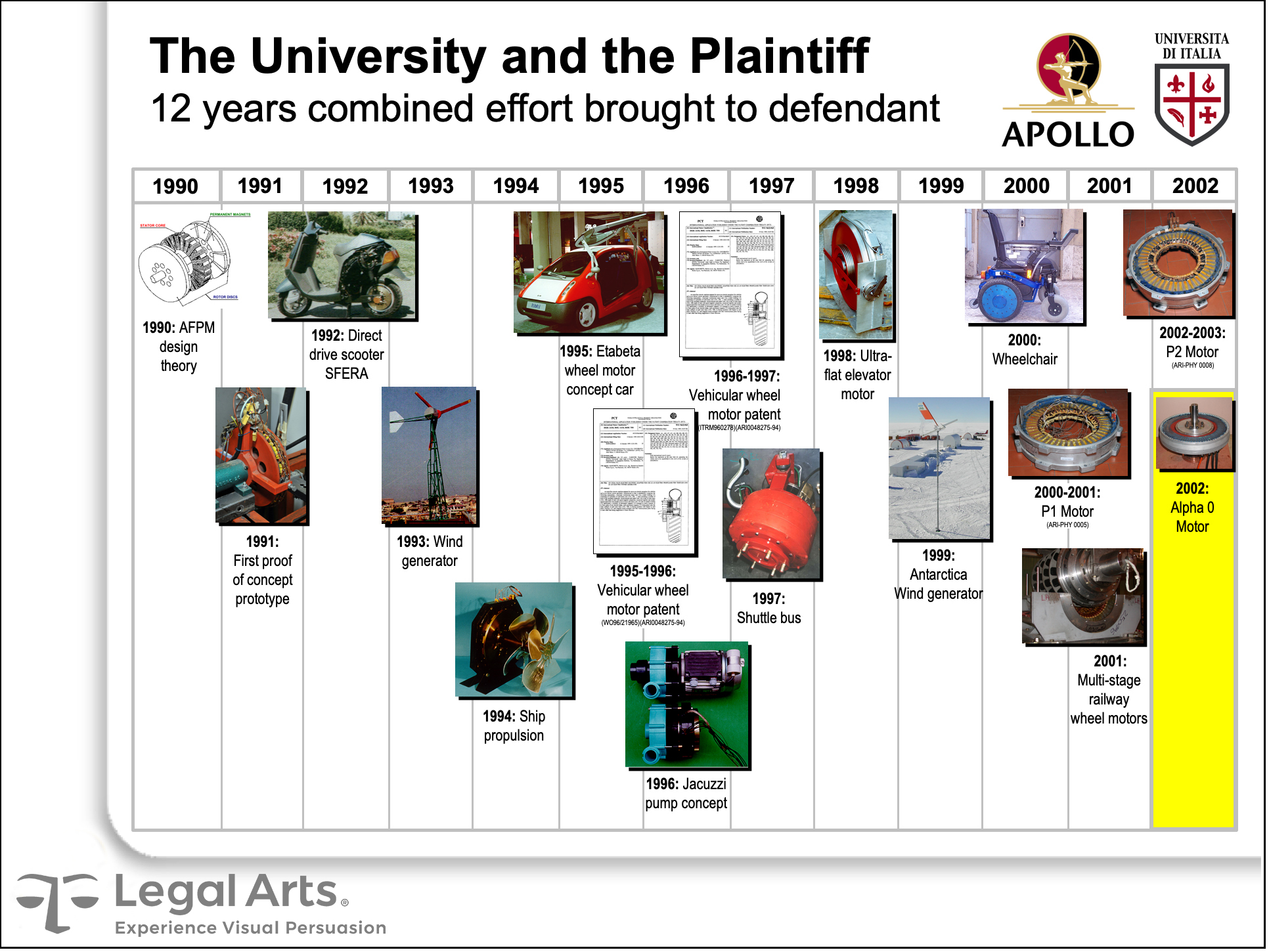

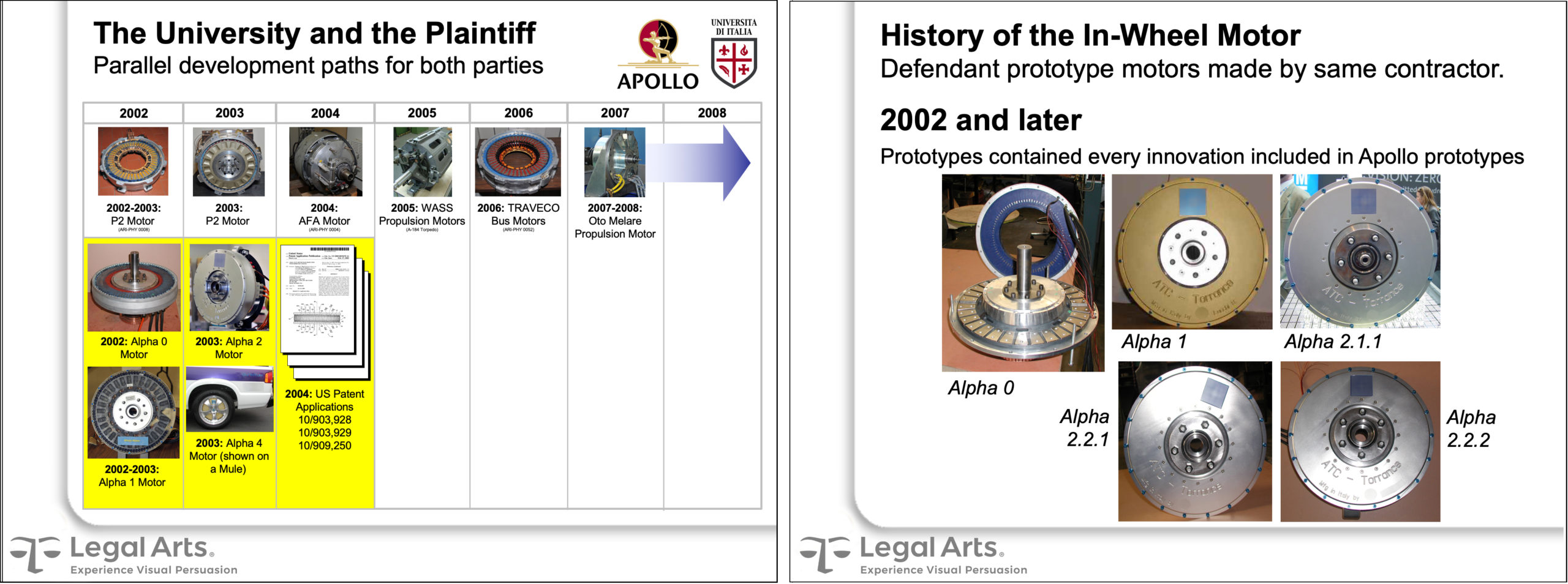

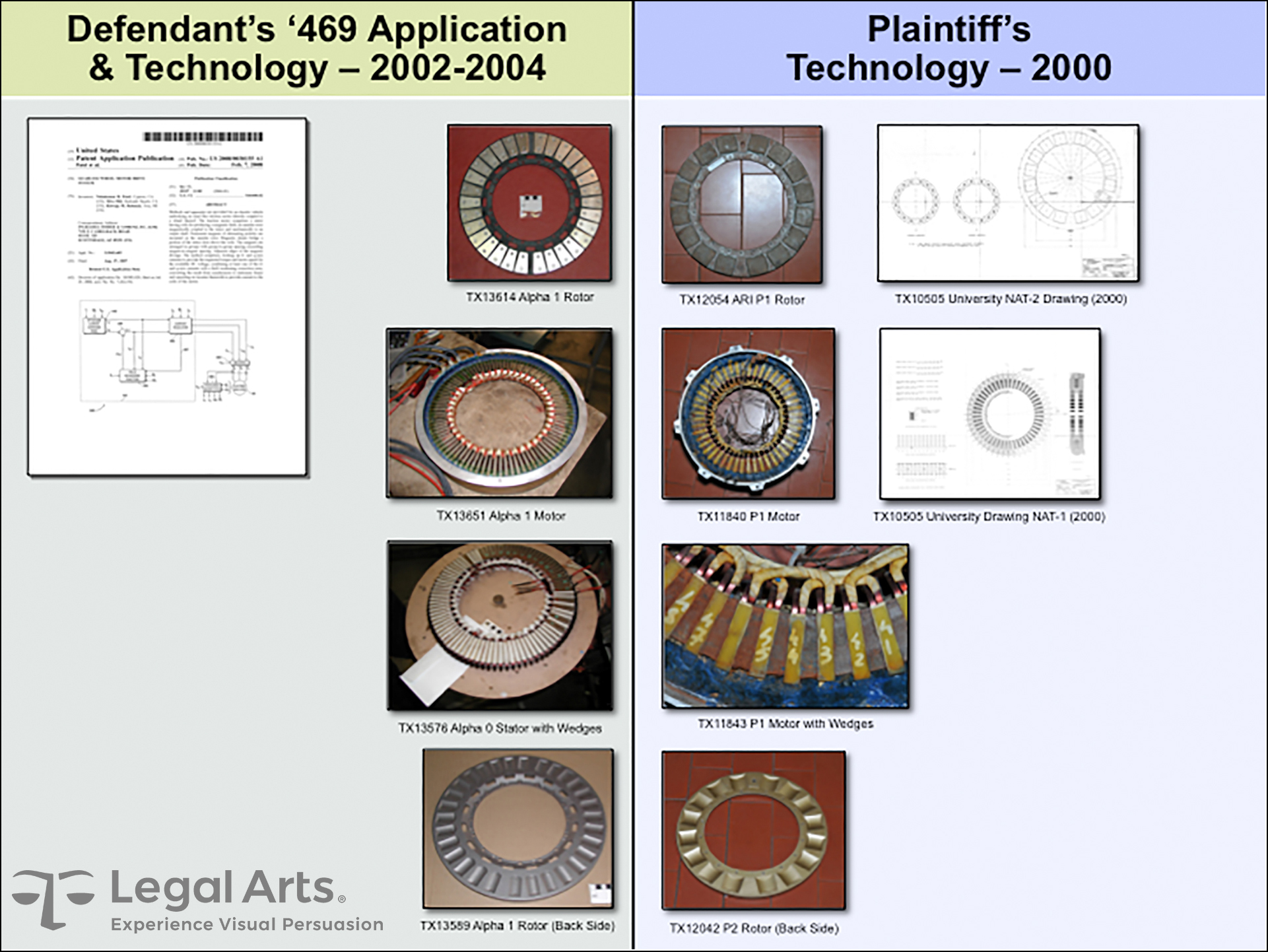

The defendant American automobile manufacturer was on such a quest when it learned of a revolutionary alternative propulsion technology promoted by two Italian academics at a European industrial forum. They reported a decade of work in their university lab perfecting the electric wheel motor, capable of powering a vehicle far more efficiently than conventional engines.

Unbeknownst to the defendant, the professors’ research had been funded for years by the plaintiff, a large Italian aerospace conglomerate.

Excited at the prospect of locking this technology up domestically and possibly internationally, the defendant induced the professors to assign away rights to use the technology in automotive applications in exchange for future R&D support.

The inventors were somewhat naïve and enamored their invention might finally reach the masses. But they were careful enough to disclose that the underlying rights to the technology were owned by the plaintiff. Despite this news, the defendant pressed on and the professors signed several English-language documents they did not comprehend.

It was not until the defendant applied for several U.S. and E.U. patents seeking monopolistic protection of several key components of all of the professors’ technology that the plaintiff learned of the fraudulent inducement to divulge the trade secrets it contractually owned.

We were engaged by plaintiff’s American counsel to help prepare for trial. Our contribution included documenting hundreds of machines and parts in Italy, developing comparison graphics of plaintiff and defense prototypes, and producing a comprehensive history of the inventions and the parties’ involvement.

The parties settled amicably on the eve of trial with the defendant agreeing to abandon the patent applications. For more information about this case, please read our case study at https://legalarts.com/case-study/automotive-trade-secret-misappropriation/

Creative tips for counsel:

- Graphical storytelling of the defendant’s motives can create and sustain righteous indignation against wrongdoing

- Consider developing a short technology tutorial to demonstrate why the misappropriated technology is perceived better than the status quo

Trade secret protection

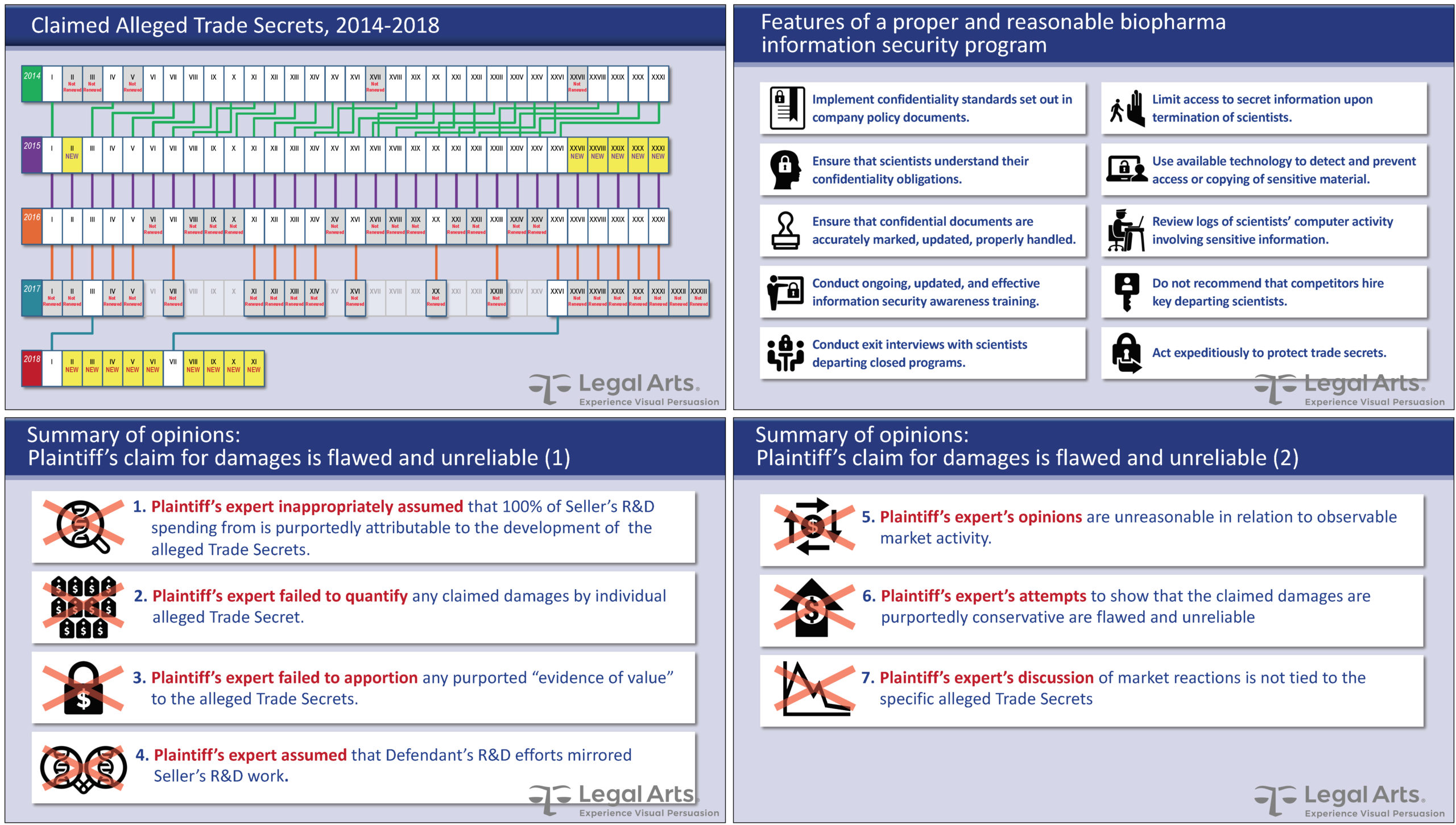

Trade secrets are only as secure as their protection. For this pharma case, two companies bid to acquire discontinued research from a large international concern. The winner then sued the loser for recruiting several scientists employed formerly by the seller and misappropriating trade secrets learned from them and during due diligence before the bid.

Our client, the defendant, defended the hiring as being responsive to the seller’s request to offer new jobs for the terminated scientists. Its misappropriation defense was three-pronged: (1) the plaintiff failed to identify the 23 supposed trade secrets originally at issue (later reduced to 2 secrets plus 9 new ones as illustrated below, upper left); (2) the seller failed to adequately protect its proprietary information after it abandoned the technology; and (3) the plaintiff’s claim for damages was flawed and unreliable.

Besides denying the use of the secrets, the defendant countersued for violation of the Sherman Act and acting in bad faith, citing the plaintiff expert’s flawed damages methodology. The case settled before trial with neither side admitting wrongdoing.

Creative tips for counsel:

- Build a checklist of protection efforts to demonstrate proper or improper compliance based on applicable law (e.g., DTSA, UTSA, or a variation)

- If chinks in the protective armor exist, compare the actual condition to reasonable alternative protections that would have maintained secrecy

For more information about trade secret graphics, please contact me at jgripp@legalarts.com.

Contents © 2020, Legal Arts, Inc.