How to Test Eyewitness Credibility with Graphic Proof

Eyewitness testimony is given great weight in civil and criminal cases even though it is notoriously unreliable. Credibility might be assumed, but without corroboration it can and possibly should be attacked. Graphic proof is an accepted method to test eyewitness credibility.

Unintentional or purposefully incorrect eyewitness accounts jeopardize fact finding and may cause false accountability for accidents and crimes, sometimes with disastrous consequences. According to the Innocence Project, mistaken eyewitness identifications contributed to approximately 71 percent of over 360 wrongful convictions in the U.S. overturned by post-conviction DNA evidence. (Innocence Project, 2020)

Research shows eyewitness believability is greatly influenced by the confidence expressed by the witness during trial testimony, whose opinions and memories (accurate or not) crystallize over time. (Handrich, 2011) Distinguishing factual from inaccurate witness accounts requires corroborating evidence and sometimes the only unimpeachable evidence to verify eyewitness testimony is graphic proof.

Common knowledge.

Remember the movie 12 Angry Men? (United Artists, 1957) The jury deliberated a murder charge hinging on the positive identification of the defendant by two eyewitnesses: a woman with poor vision and a man who walked to the witness stand with a slow limping gait

The man’s credibility was tested when one juror, portrayed by actor Henry Fonda, questioned the man’s veracity. The man testified he took fifteen seconds to walk from his bed, where he heard a body fall to the floor, to a stairway where he saw the fleeing defendant. But Fonda’s shuffling reenactment took 41 seconds to walk the 55-foot distance as measured on the to-scale diagram entered into evidence.

If this was a real case tried today, we’d have more precise tools at our disposal to test the witness’s credibility, but the takeaway would be the same: eyewitness testimony should be corroborated to be believed. In this post, I illustrate a few examples of graphic proof used to validate or impeach eyewitness testimony and visibility issues.

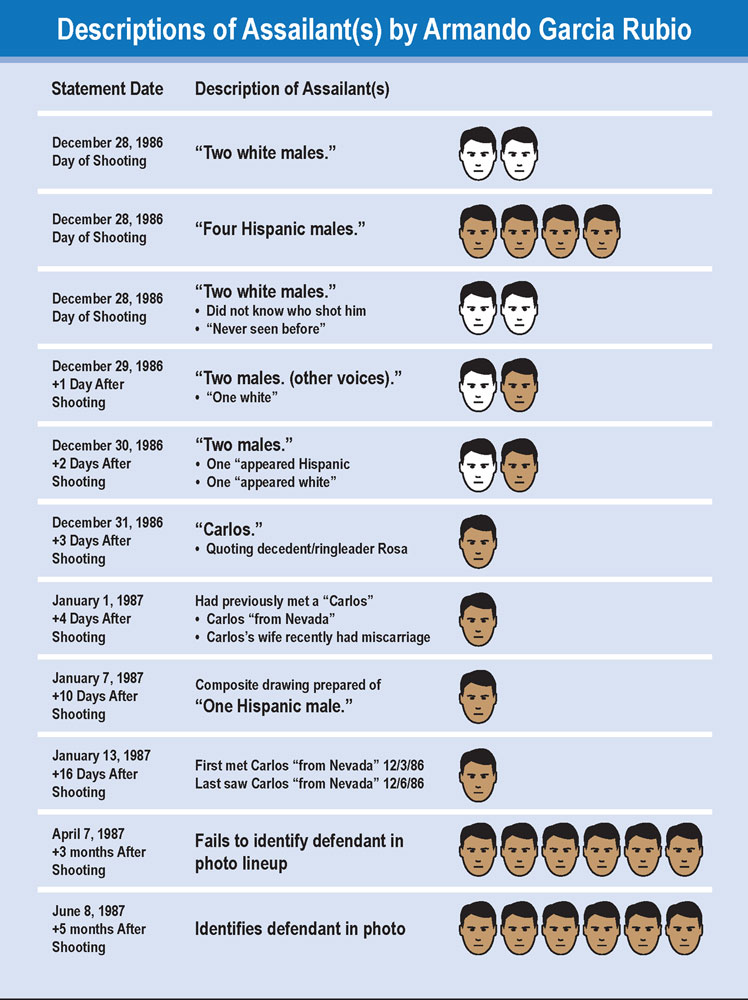

“Two white males.”

Lawyers rarely expect eyewitness memory to improve over time (despite the research cited above) unless photo spreads or line ups jog witness memory. Memory for faces decays with passing time, rapidly in the first few hours and gradually thereafter. (Wells, 1988)

In this case (People v. Carlos Fonseca, CR88634), at least two males entered a residence to buy heroin. Inside were five people including the ringleader of the drug gang, a former girlfriend of a rival dealer named Carlos. According to the lone survivor the visitors executed her and the others, with the woman alone shot multiple times.

The survivor’s description of the assailants was initially “two white males.” However, he changed his descriptions so often that police did not make an arrest for over five months. Multiple shooters were identified as people of different races: only Caucasians, only Hispanics, a Caucasian and a Hispanic, and eventually someone named “Carlos.”

In his eleventh questioning and a second photo spread, the survivor identified an individual he knew casually before the attack, “Carlos from Nevada,” a low-ranking gang member and not the rival drug dealer. Was the survivor telling the truth this time, or was he afraid to identify the correct Carlos?

Based largely upon this information, the defendant—Carlos from Nevada—was arrested, charged, and ultimately convicted of four murders and the attempted murder of the survivor. It is uncertain whether the jury every questioned his credibility as a witness.

“I saw everything.”

A civilian ride-along with a literal front-seat view from inside a patrol car claimed to witness the defendant shoot two police officers before she was shot and wounded (People v. Sagon Penn, CR74094). She testified she “saw everything:”

- the defendant lying on the ground parallel to the car with his head toward the front struggling with the officer straddling him

- the defendant pulling the officer’s revolver from his holster, pointing it at the officer’s neck, and shooting him

- the defendant, still supine, turning the weapon on the second officer and shooting him fatally

- the defendant standing, turning the weapon toward her, and firing through the closed driver’s side window

About a year after the incident, the defense forensic scientist and I produced a reenactment of the shooting to test over thirty eyewitness accounts to prepare for trial. The physical evidence, police reports, and our own scene documentation enabled us to reconstruct the scene accurately and a recorded 9-1-1 call enabled us to time the shots within a 6-second span.

This photo was taken from the ride-along’s viewpoint at the moment the officer on the right was shot in the neck. It demonstrates she was mistaken about positioning parallel to the car and her ability to see the defendant’s actions, the kneeling officer’s holster, and the revolver pointed at his neck.

After a mistrial, and before the start of the second trial, the witness applied for Navy housing and the housing agent, who recognized the applicant from the highly publicized trial, secretly recorded their conversation and captured the witness saying she “didn’t see a thing.” The recording was admitted into evidence in the second trial. After another mistrial, after which all charges against the defendant were dismissed.

Two eyewitnesses versus gravity.

The defendant was convicted of murdering a man in an unprovoked stabbing on a rainy street, late at night, in a beach town (People v. David Genzler, SCD120238). The decedent’s girlfriend and an acquaintance eyewitness told police the defendant chased her and the decedent down the street before knocking him to the ground and then straddling, beating, and then stabbing the decedent in the chest, causing blood to spurt out and up onto the defendant’s chest.

The defendant claimed after seeing him offer a ride to the girlfriend, the decedent became aggressive, wrestled the defendant to the ground, pinned him prone, and violently pulled his head back. Fearing great physical harm, the defendant extracted a pocketknife from his right front pocket and stabbed blindly over his right shoulder. The knife penetrated the decedent’s chest and perforated his aorta. The decedent then stood and bled down onto the back of the defendant’s right shoulder and around to the chest as he rotated to face the decedent while still on the ground.

For the defendant’s retrial, I was hired by the defense to prepare an animated reconstruction of the stabbing graphically demonstrating the expert pathologist’s testimony how:

- the victim’s wound would have seeped—not squirted—blood;

- blood transfer onto the defendant’s shirt could only occur with the decedent above the defendant;

- the blood pattern was consistent with the defendant’s story he blindly stabbed backward over his right shoulder while lying prone on the ground and then rotating around to face the decedent;

- eyewitness testimonies contradicted the physical evidence.

The jury believed the defense version and found the defendant guilty of manslaughter instead of murder. He was sentenced to serve six months besides time served.

The lead prosecutor and D.A. investigator were later reprimanded for misconduct and sued in federal court for pressuring the decedent’s girlfriend to testify falsely about several issues. This case was featured in the television show Forensic Files. (Forensic Files, 2004).

Conclusion.

Testing eyewitness and percipient witness testimony cuts both ways. Sightlines, potential view obstructions, distances, and duration are common variables verified or disputed with graphic proof. If you’d like to learn more, drop me a line.

Jim Gripp is a pioneering founder of Legal Arts, Inc. He has over forty years-experience as a litigation graphics consultant and private investigator. Email Jim at jgripp@legalarts.com.

Endnotes

Forensic Files “Pinned by the Evidence,” Season 9, episode 8, air date 24 August 2004. © MedStar Television.

Handrich, Rita “Helping jurors ‘see’ what eye witnesses said they saw,” last retrieved 28 March 2020 at http://keenetrial.com/blog/2011/11/30/helping-jurors-see-what-eye-witnesses-said-they-saw/?goback=.gde_2006395_mem

Innocence Project, “Eyewitness Misidentification Reform,” last retrieved 28 March 2020 at https://www.innocenceproject.org/eyewitness-identification-reform/

United Artists, copyright 1957 (licensed from Alamy.com).

Wells, Gary L. Eyewitness Identification: A System Handbook, Carswell, 1988. Last retrieved 28 March 2020 at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239986483_Eyewitness_Identification_A_System_Handbook